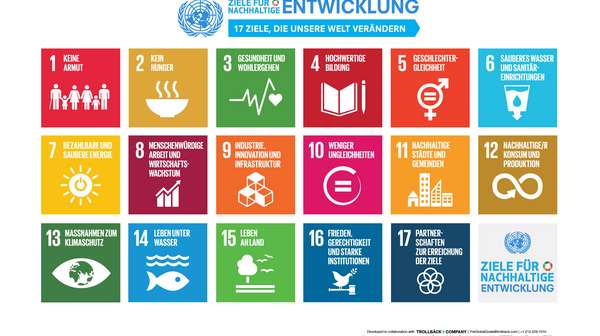

With the 2030 Agenda, 193 countries have committed to ensuring that all people can live in dignity by 2030.

Sustainable Development Goals' Current Status

Stagnation in the Face of Multiple Crises – interim report of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and review of the 2023 SDG Summit held in New York on September 18-19

As the world reached the halfway point in its journey to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, heads of state and ministers gathered at the SDG Summit in New York last week. Since the 2030 Agenda was signed in 2015, the SDG Summit takes place every four years in the framework of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), this year more than ever amid pressing global challenges such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the aftermath of the Covid 19 pandemic, and the increasingly tangible climate crisis.

The Sustainable Development Goals' current status: A mere 12% of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are currently on track or as the newest Global Sustainable Development Report 2023 summarizes progress on the 2030 Agenda it is a "stagnation in the face of multiple crises". The goal of the summit was to "provide high-level political guidance on transformative and accelerated actions" to achieve the SDGs by 2030.

Mid-term review of the 17 goals

With regards to ending hunger, which is covered by the agenda’s second SDG, the latest "State of Food Security and Nutrition 2023" (SOFI) paints a concerning picture: 735 million people are suffering from hunger and estimates show that this number will still be around 600 million in 2030.

In absolute numbers, this is even slightly more than in 2015 when the 2030 Agenda was adopted. And while it is true that Covid-19, Russia’s war in Ukraine and its consequences have played their part, research shows that we wouldn’t be on track even without these crises (GSDR 2023). As ending hunger has become a distant prospect, guidance on “transformative and accelerated actions” is urgently needed.

Sustainable Development Goals Summit Outcomes

The Summit’s main result is a political declaration which has, in some ways, exceeded the aspirations of its older sister, adopted in 2019. It emphasizes that we need to speed up our fight against hunger and consider entire food systems. Most importantly, maybe, it features the human right to food. That is a welcome pat on the back for those who have for years advocated for a human rights-based approach in fighting all forms of malnutrition.

Whoever was expecting concrete financial commitments will, however, be deceived. They did not make it into the final document. Still, developed countries are urged to fulfil their ODA commitments: At least 0.7 per cent of their gross national income (GNI) should be dedicated to official development assistance (ODA).

As aid should go where it is needed the most, the declaration also urges developed countries to dedicate at least 0.2 per cent of GNI to the so called least developed countries (LDCs). As these targets have been there since the 1970s but on average remain unreached, this is an important reminder that, amongst other resources, we do need public development finance to reach the SDGs.

In addition, states committed to advance the UN Secretary-General’s idea of an SDG Stimulus, albeit without putting a number to it. Guterres’ goal is to mobilize $500 billion USD annually, mainly via multilateral development banks, to tackle the high cost of debt and related risks. This can for instance be done by converting short-term high-interest loans into long-term loans with lower interest rates. That the stimulus remained in the declaration, is interesting: The news outlet Devex had reported in the run-up to the summit that the US and a small group of its allies wanted to limit the UN's power in financial reform and therefore tried to exclude the stimulus from the final text.

In the broader scheme of things, which is an increasingly divided and multipolar world, the fact that a political declaration containing a recommitment to the 2030 Agenda was unanimously adopted, is a silver lining. Of course, a UNGA declaration, that is by definition non-binding under international law, cannot be the only tool to accelerate progress on the SDGs. Still, it is an important step in the right direction and a text that can and should be used to guide leaders and hold them accountable.

Agenda 2030: From Political Intent to Action

While progress in the political declaration is positive, ultimately, the success of the SDG Summit depends on actual implementation. The political declaration needs to be translated into measures which in turn need to improve the situation of those most affected by hunger, tackle food systems comprehensively and realize the human right to food.

Welthungerhilfe Calls for Course Correction in Fight Against Hunger

On a general level this means that accountability for the 2030 Agenda needs to be improved: many SDG indicators remain inadequate because data is missing and they fail to define words like “sustainable” (for instance indicator 2.4.1: Proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture), and data is missing. This means we only partly know where we stand. This makes it harder to identify gaps and set priorities. Moreover, research shows that governments need to better integrate SDGs into their policy making.

Parliaments and civil society play an important role in holding leaders accountable and need to be included in decision-making. One way to do so would be to not only have national plans, but subnational and industry specific plans to overcome stagnation, as the GSDR 2023 recommends. Plans should also be industry-specific to ensure that the private sector, which should play a central role in reaching the SDGs, also assumes its responsibility for the 2030 Agenda.

What does this mean concretely? The Voluntary Guidelines to support the progressive realization of the right to adequate food, who will turn 20 next year, provide guidance. Guideline 8, for instance, underlines that states should facilitate access to resources such as land, water or livestock, taking particular attention to the specific problems vulnerable groups are faced with. Women’s rights to inherit their husbands’ property for instance continue to be denied in more than 100 countries, negatively affecting their access to land.

Another example is Guideline 3.8, which states the importance of governments involving civil society and other key stakeholders, including small-scale farmers and the private sector. If a government issues a new policy on fertilizer subsidies, they need to involve those most affected, civil society as well as those producing and providing fertilizer. This is key to e.g., ensure that subsidies reach those farmers that really need them, that they do so at the right time in the season and that agroecological alternatives and soil health are discussed and taken into consideration. Participation is a question of justice and a key element to ensure that policies are effective and that they are accepted.

Realizing the human right to food must be priority

Governments and continental unions such as the European and the African Union have the prime responsibility of putting policies in place and ensuring their implementation to prioritize the realization of the human right to food. Governments of countries affected by hunger need to ensure they address inequalities within their country, including providing the necessary investments in agriculture and rural areas. African Union member states, for instance, have promised to invest at least 10 per cent of their national budgets into agriculture. A share that is, as the 0,7 per cent ODA goal, seldom reached.

Donors, on the other hand, need to live up to their financial commitments. This includes the 0.7 per cent and 0.2 per cent goals referred to above. Germany currently still fulfils the former but fails to reach the latter. However, the recent budget act submitted by the Federal Government to the parliament includes budget cuts from 2024 onwards, including a cut of 1 billion EUR in humanitarian assistance and crisis prevention. These are funds often going to least developed countries.

SDG Status: Goals are at risk from cuts

These planned cuts will have direct consequences for people in need. Taking a Welthungerhilfe (WHH) project in Niger as an example, WHH would no longer be able to distribute food aid and improve the access to clean water to the extent it is doing so now. Niger is deeply affected by climate change and currently over four million people in Niger are in dire need of humanitarian aid. To continue to be seen as a reliable partner, the German government and other high- income countries must thus ensure stable development financing in the short, medium and long term. This includes living up to their historic responsibility for the climate crisis.

Additionally, there is an urgent need to tackle the high cost of debt and provide affordable financing sources, as planned under the SDG Stimulus. Many low-income countries currently spend a large part of their budgets on interest payments. A lower interest burden is key for these countries to be able to build up social security systems, which are key to ensure that people have enough income to pay for food when they get sick or lose their job.

Finally, the UN and the 193 member states that signed the 2030 Agenda need to keep its spirit alive which mainly means moving from political intent to action. With sufficient political will, international cooperation, and financial resources, it can still be done or at least a lot better than now. The Summit of the Future, co-facilitated by Namibia and Germany and planned for September 2024 will be the next important milestone to hold leaders accountable.