The 2023 Global Hunger Index: Progress on Hunger has largely stalled

In the face of multiple crises, progress on hunger has largely stalled, and large demographic groups such as youth, especially in low- and middle-income countries, are disproportionally affected.

This year marks the halfway point of the Sustainable Development Goals, leaving only seven years to achieve SDG2 Zero Hunger. As the year 2030 looms, nearly three-quarters of a billion people are still unable to exercise their adequate right to food. While there have been many years of advancement, progress in reducing hunger worldwide remains largely at a standstill. Hunger is not new and neither are its drivers—so why is the world falling far short of what is needed to achieve Zero Hunger?

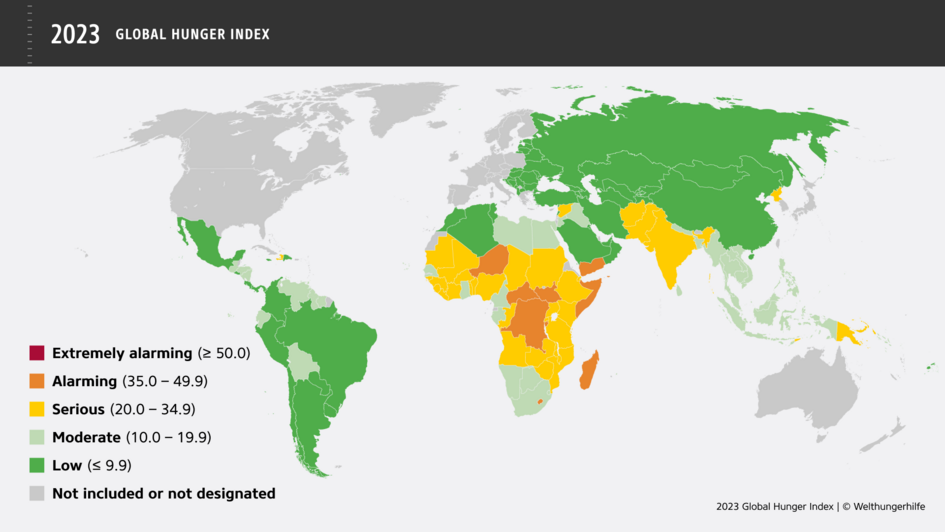

On 12 October, Welthungerhilfe (WHH), together with Concern Worldwide, launched this year's edition of the Global Hunger Index (GHI). The 2023 report paints a worrying picture: the global GHI score for 2023 is 18.3, less than one point below the GHI score of 19.1 for 2015—the year the SDGs were implemented. In recent years we witnessed an increasing number of undernourished people across the globe, from about 572 million in 2017 to about 735 million. These trends clearly show that extraordinary efforts are needed to jump-start the fight against hunger and ensure the right to food for all people, including the millions who now go to bed hungry every night.

Can we still achieve Zero Hunger by 2030?

In recent years, we have seen global summit after global summit—including the COPs, the UN Food Systems Summit, and the SDG Summit—where promises were made and hands were shaken to signify commitment to achieving a better life for people and the planet. Instead, however, we are witnessing the reversal of decades of progress. So what has happened—or not happened? And what must be done to get back on track? Do we still have time?

The Global Hunger Index aims to shed light on these questions while emphasizing the need for urgent action now!

What is the Global Hunger Index?

The Global Hunger Index is a peer-reviewed report published by Welthungerhilfe and Concern Worldwide on an annual basis. Since 2006, the series has measured and tracked long-term trends of hunger on a global, regional, and national level. The report also raises awareness of the scale and scope of hunger across the globe with the aim of providing incentives to act.

The GHI measures hunger by combining the following four indicators:

Undernourishment: the share of the population whose caloric intake is insufficient

Child stunting: the share of children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition;

Child wasting: the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition; and

Child mortality: the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, reflecting in part the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments

Considering all these different indicators, the Index measures not only the availability of calories but also takes into account diet quality and utilization of food. In this way, the GHI is able to measure the multidimensional character of hunger.

For more information, check out the Methodology on our website: Methodology - Global Hunger Index (GHI).

What is the 2023 GHI report telling us about the hunger situation in the world?

The 2023 report shows that global progress in reducing hunger has largely come to a standstill since 2015. In 43 countries, hunger remains serious or alarming, according to the GHI estimates, with a particularly worrying situation in Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia. With the current trajectory, 58 countries will not even achieve low hunger—much less zero hunger—by 2030.

Nine countries have alarming levels of hunger: Burundi, Central African Republic, Madagascar, Yemen, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Niger, Somalia, and South Sudan.

The crises have aggravated inequalities between regions, countries, and groups

Looking at the impacts that led to this reversal of progress, we can see a situation of so-called polycrisis unfolding around the world. The compounding impacts of climate change, conflicts, economic shocks, the global pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war have exacerbated social and economic inequalities and slowed or reversed previous progress in reducing hunger in many countries.

While some countries have shown resilience in the face of the current crisis, others have experienced deepening hunger and nutrition problems. Low- and middle-income countries have been particularly hard hit relative to high-income countries. And large demographic groups such as women and youth are carrying the burden of these crises.

Current food systems are failing young people

These developments lay bare that current food systems are unsustainable, inequitable, non-inclusive, and vulnerable to environmental degradation and the dangerous effects of climate change. At the most basic level these food systems are not able to provide all people with sufficient nutritious food.

The current global youth population, estimated at 1.2 billion, is the largest in history. In many parts of the world, young people face a set of stark realities. They are more likely than adults to be affected by extreme poverty and food insecurity. And gender also plays a role in youth hunger and undernutrition: young women are particularly affected, and gender inequality aggravated by unpaid car work, despite the importance of women’s health and nutrition status for future generations.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected young people, who are particularly vulnerable to job losses and crises. Globally, more than one in five young people are not in education, employment, or training. Unemployment is three-times higher among youth compared to adults and young people are more likely to be informally employed.

Employment in the agrifood sector is often more accessible for young people because of low entr requirements in terms of capital and skills. However, for many youth, farming is considered an occupation of last resort and low productivity. They often lack access to the resources, land, skills, and opportunities that would enable them to productively engage in food systems. These barriers, coupled with the lack of food sovereignty, including the loss of indigenous and local farming and knowledge systems and restricted access to seeds, have turned many young people away from agricultural and rural livelihoods.

While young people will inherit these food systems that are unable to meet the needs of people and planet, their participation in making decisions that will affect their future is limited.

Youth must play a central role in transforming food systems

To unlock the power and potential of youth in shaping food systems, their capacities must be strengthened, and agriculture and food systems need to offer attractive and viable livelihoods. Investments are needed in young peoples (vocational) education, health, and access to resources, such as credit and land. Rural economies must be diversified, and investments should focus on creating non-agricultural jobs in the entire food system – with decent wages and employment conditions.

Already now, young people worldwide are forming their own organizations and initiatives, reshaping perceptions of global challenges while driving social innovation and demonstrating a willingness to be part of the solution. Now they must be heard and involved in decision-making. Meaningfully engaging youth as leaders can unlock their potential as innovative agents of change and harness their energy and dynamism to transform food systems.

The actions we take now—and those we fail to take—will determine future food system outcomes, but it is today’s young people who will live with these outcomes for decades to come. Embracing a long-term perspective and putting the right to food and food sovereignty at the heart of food systems solutions will help reflect young people’s livelihoods, options, and choices and ensure generational justice.

Despite the challenges, there are examples of progress and hope

The 2023 Global Hunger Index reveals a sobering reality and underscores the urgency to act to tackle hunger on a global scale. But it also shows that decisive action pays out.

Despite the challenges facing the world and the recent stagnation in hunger levels at the global level, some countries have shown remarkable progress since 2015.

With increased efforts, we can build a future where everyone has access to nutritious food and where young leaders drive lasting change in our food systems.

The forces of climate change and inequality are changing the world. It is vital that governments do much more to end hunger by 2030 and work beyond that to transform food systems. An exceptional effort is needed to ensure that the right to adequate food is respected, protected, and fulfilled, not only for the millions of people who currently go to bed hungry each night but also for the billions who will shoulder the burden of crises not of their making—the worsening impacts of conflict and climate change—far into the future.

Most importantly, beyond increasing our efforts to meet a target, we must always keep in mind the human realities behind these numbers and figures. Current humanitarian needs, of course, are immense and must be met, but we also need to recognize that the speed and severity of this expanding hunger are due to the fact that millions of people were already living on the edge of hunger—a legacy of past failures to build more equitable, resilient, and inclusive food systems.