Europe can only score points with developing countries if it sees eye to eye

If the EU wants to credibly offer a fair partnership distinct from Russia and China, it must restore trust, take priorities seriously, fund more effectively, and increase labor migration.

The European Union (EU) has a unique role to play in promoting sustainable development in developing countries. EU institutions and member states together are the largest donor in the world and have considerable influence in developing countries. In addition, countries of the bloc form one of the largest economies in the world, host a large number of international organizations and a wide range of European policies, from migration to climate and beyond, have significant spill-over effects on developing countries. Yet, with heightened geopolitical tensions shaping the development landscape in ways that will have grave consequences for the future of international cooperation, the burning question is whether the EU and developing countries can establish more equal and effective partnerships.

The EU’s relationship with many of its partner countries is strained. Too often, policymakers in developing countries see little substance behind the public assurances by European policymakers of wanting to create equal partnerships. Populist rhetoric in Europe, including on the use of aid to deter migration and the legitimacy of development assistance in a world where domestic priorities are insufficiently funded, continues unabated. In partner countries, governments and publics resent what they see as paternalistic instruction and often coercive conditionality on the use of assistance.

Trust in development cooperation is low with broken promises, double standards and bifurcated approaches, not least as a result of the continued hold-up of the post-Cotonou agreement from the EU side, the failure to act on the problem of unsustainable debt, the not so distant memory of European vaccine “nationalism” during the COVID-19 pandemic and the different standards some Europeans apply with regards to fossil fuel exploration. Some countries in the Global South charge Europe with hypocrisy for sanctioning Russia while failing to protect them from the resultant costs, including surging food, fuel and fertilizer prices. The lack of trust is increasingly compelling countries in the Global South to choose sides, dividing the world at a time when the list of global challenges is soaring and is dependent more than ever on collective action.

The scale of both migration and displaced populations has again become a major source of domestic political tensions in Europe. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU triggered its temporary protection mechanism for Ukrainians fleeing the war. It grants forcibly displaced people legal status and access to the labour market, social benefits and education for one year (renewable for up to three). However, European countries still disagree on how to create a system that applies to all asylum seekers, not only those from a predominantly white, friendly country.

The situation in many European countries illustrates the bifurcated approach: Ukrainians are welcomed with supportive rhetoric, while other refugees are still quietly subject to a system that prioritizes keeping refugees out and still has no settled agreement on how to distribute arrivals. This has compounded the view that is shared across the African continent – that some armed conflicts are deemed to deserve attention while many of the conflicts in Africa are treated with a lack of resolve.

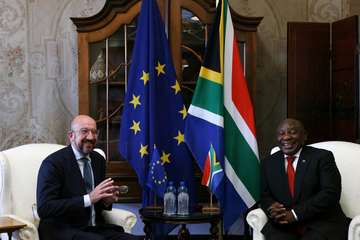

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took place one week after the 6th EU-Africa Summit where the two sides had one common goal: to press the reset button on the EU’s relations with Africa after years dominated by mistrust, a mismatch of expectations, and anxiety. With the launch of the Global Gateway—the EU’s €300bn global infrastructure investment package, half of which was earmarked for Africa—the EU had been at pains to present itself as a priority partner for Africa. The concept of “strategic autonomy”—the idea that the EU should be able to do and say what it wants, without being constrained by other powers—comes to the fore in the Global Gateway strategy and has come to shape the new storyline on EU development cooperation.

The narrative is built around the following elements: globalization comes with risks; the EU needs to reduce its dependencies; energy is key (especially in Sub-Saharan Africa); and so, the EU needs to build strategic corridors with partner countries to reinforce its own strategic autonomy. But ask developing countries what they prioritize, and the answers are education, health, and employment. At this time of unprecedented challenge, the EU has put its own interests ahead of the urgency of action and investment to deliver on developing countries’ immediate needs and priorities.

Restoring trust

EU development cooperation is undoubtedly being affected by escalating geopolitical tensions. But development cannot occur without trust. To build trust with its partners, the EU must listens to them and must not lose sight of their own development needs and priorities. It must ensure that its policies towards its partners are credible and aligned with its core values. This requires a comprehensive approach to addressing structural global challenges on the one hand, and poverty and vulnerability challenges at the country level, on the other, alongside strengthening contingency finance and stabilization capacity to keep crises from worsening and spreading.

Crucially, in this difficult geopolitical environment, if Europe credibly wants to offer developing countries a long-term partnership of equals, and distinguish itself from others, in particular China and Russia, it will need to ensure that its policies are transparent and that it can be held accountable by its partners.

Here, we look at two areas where Europe’s policies have significant spill-over effects on developing countries and how to change these policies to become more credible and sustainable.

Spiraling needs and dwindling finance

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, the devastating effects of climate change and extreme weather and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have fueled debt crises, humanitarian and refugee crises, the resurgence of global poverty and the widening of inequality. Food and energy have become weaponized by the war in Ukraine, sending inflation soaring to levels not seen in decades. The shocks have hit all countries, but they have hit developing countries particularly hard.

The effects of climate change are becoming more severe and at a much faster pace than many had anticipated. In the areas of most acute deprivation, chronic poverty and environmental shocks compound each other. While the African continent generates only 4 percent of global emissions, it is experiencing the most severe impacts of climate change. And yet, it receives a mere 12 percent of the finance needed to manage climate change.

Official development assistance (ODA) now accounts for 84 percent of bilateral climate finance. Despite the intention for climate finance to be “new and additional”, nearly half is re-badged, or has come from stopping other aid programmes and most of it is spent on climate mitigation projects in MICs. In 2022, at COP27 in Egypt, the EU proposed the establishment of a loss and damage fund for countries vulnerable to climate-related disasters, resulting in a breakthrough for climate justice. Although providers have pledged over $300 million, the money continues to remain elusive.

Confronted with insufficient liquidity to respond to these challenges and unable to access global markets, LICs need ODA now more than ever. Yet, European countries are operating under constrained budgets following an increase in energy, defence and refugee spending and adverse political environments. While development aid from the EU Member States rose in 2022, largely because of higher in-donor refugee costs, the tense economic and political situation in 2023 offers little room for outright aid increases.

This year, ODA from EU Member States is expected to either plateau or decrease, with countries like Sweden and Germany proposing a reduced envelope for development. And as for the EU’s own development budget, it has a maximum ceiling of €79.5 billion until 2027, most of which has already been programmed. Yet, with a full-scale war on its borders, the EU will be hard-pressed not to continue to give priority to Ukraine.

Potentiate the effect of financing

The EU’s Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument–Global Europe (NDICI Global Europe), adopted under the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework together with the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+) and the External Action Guarantee (EAG), provides a set of mechanisms for grants, blended finance and guarantees to scale investment for greater impact in developing countries. With the massive scale-up in the use of guarantees for energy and transport in particular in MICs, fewer financial resources are being provided in the form of grants for basic needs in LICs.

With the costs of reconstruction of Ukraine multiplying by the day and European development budgets in decline, the EU needs to leverage its development finance by deploying its financial instruments in a smarter way to provide vital support to countries in need. Currently, the mainstream use of 100 percent grants by the European Commission as part of its €2 billion per annum budget support programme means MICs with moderate or better market access tend to get more grants than they might require. At the same time, the EU deploys its Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA) instrument, which provides medium- and long-term concessional loans to countries to help them deal with balance-of-payments difficulties. However, this instrument is only deployed in the EU’s neighbourhood.

By reappraising its mix of concessional and non-concessional funding, the EU could use its grant finance in a smarter and fairer way so that it creates leverage where it is needed most.

A development partnership on migration

The EU and developing countries have the potential to create mutually beneficial partnerships that will not only benefit a large share of the world’s population, but also address some of the most pressing issues facing the world today.

Take migration. Europe faces a major demographic challenge with an aging population and a shortage of workers, in particular in key sectors such as healthcare, construction and jobs related to the green and digital transitions. A study by the European Parliament calls the shortage of workers in green sectors “enormous” while in Germany alone, the working age population is estimated to decrease by 17 percent until 2050. Roughly 400’000 migrant workers a year will be required to fill labour gaps. At the same time, and unlike the rest of the world, Africa will experience a rapid population growth: the “entire world’s prime-age working population will increase by 428 million between 2020 and 2040. Of that increase, 420 million will be in Africa”.

Europeans should embrace this development and support Africans’ access to education and decent jobs overall. A limited number of young people could then support Europe’s labour market. Instead, many European member states’ approach to migration remains restrictive at its core and limited to the prevention of illegal migration through strict border controls, a restrictive visa policy and a focus on returns of failed asylum-seekers.

While many European states acknowledge the need to attract skilled workers, the EU lacks a common migration policy that enables the continent to meet these challenges of the future. Also, legal pathways are not used at scale. Instead, many European countries are spending development funding on projects addressing the root causes of migration, effectively aiming to reduce migration even though evidence suggests otherwise. The available evidence demonstrates that development assistance has very limited effectiveness in deterring migration. Development progress witnessed in numerous previously impoverished nations has often resulted in a rise in emigration. Consequently, the evidence suggests that donors could potentially achieve more significant outcomes by utilizing aid not to discourage migration, but to shape it for the benefit of all parties involved. However, in contrast, there is also a strong move towards tying aid to the willingness of partner countries to readmit their nationals if their asylum application has been rejected.

European migration agreements with partner countries should go beyond the current approach mainly focusing on development aid, readmission and returns and instead include a wider range of policy areas such as trade, climate change adaptation, migration and financing infrastructure and human development. A common EU-wide approach to collaborating with third countries on migration specifically would aim to scale up labour market migration, ensure people escaping persecution can legally and safely apply for asylum, and enable a more effective approach to returns.

Legal pathways can be designed in a way that constitutes a triple-win, benefiting countries of origin and host countries while empowering migrants. “Global Skill Partnerships” meet global skill shortages by providing targeted training in countries of origin and helping some of the trainees move. They are flexible, tailored to local labour market needs, combat “brain drain” by training workers for the needs of the countries of origin, give migrants employment rights, and enable the country of destination to manage migration legally. Some European countries like Belgium and Germany, recognizing their labour market needs and skill shortages, have already implemented Global Skill Partnerships. In the future, these should be scaled across the continent.

The way forward

To create a long-term partnership of equals between the EU and the developing world, it is imperative to rebuild trust, address structural global challenges, and prioritize the immediate needs and priorities of developing countries. This also means that the EU hast to start speaking with one voice and find greater coherence among its member states.

As Niels Keijzer points out in his article on the Post-Cotonou agreement, there is a need to build long-term alliances to achieve sustainable development. The delay in signing the agreement, mainly due to the hold-up by certain EU member states, and the debates surrounding it, illustrate some of the shortcomings of the EU’s approach to developing countries.

On a more practical level, Team Europe, joint activities between the EU, its member states and development finance institutions abroad, is an opportunity for member states to collectively respond to the needs of partner countries. However, questions remain about the implementation of Team Europe Initiatives and how these initiatives ensure they are not driven by the interest of big member states alone.

The new EU leadership appointed next year will have to adopt credible, transparent and accountable policies, leverage development finance effectively, and embrace a comprehensive approach to migration. Only then can the EU establish a partnership that benefits all parties and make an effective contribution to global cooperation.