Hidden Costs of Food: Sustainable Change Needs Sustainable Economic Systems

A FAO-Report gives an idea of the side effects of food production in social, ecological and heath terms. But how can change be achieved?

Food ensures our physiological survival. But its production, distribution and consumption also have far-reaching economic significance. This varies greatly depending on the point of view: Agricultural industry, for instance, can be credited with securing the jobs of more than a billion people in the cultivation, the processing of agricultural products into food and their distribution. From another perspective, the crucial importance of smallholder agriculture for the livelihood of 2.5 billion people is emphasised – to feed themselves as well as city dwellers through local markets.

From various perspectives, the importance of the sector for well-being, for social relationships, for income and for the utilization of natural resources is presented, based on its relevance for the gross national product. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates the global output of the food industry at USD 9 trillion in 2020, or around nine percent of global economic output.

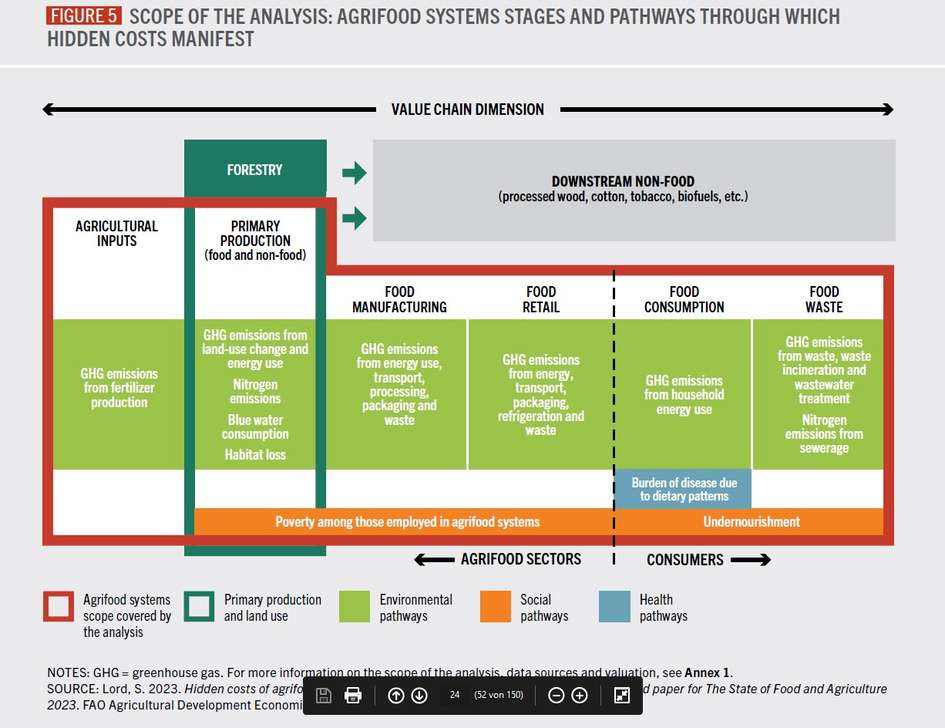

However, this classic economic view systematically neglects the hidden costs of economic activity. Economic activity in its entirety – and therefore also the global food system – causes ecological or health-related costs that are not included in conventional accounting. All these side effects, such as environmental pollution, loss of biodiversity, global warming or nutrition-related diseases, including treatment costs for cardiovascular diseases or type 2 diabetes, are referred to as hidden costs. In addition, social costs resulting from low wages are also externalized in the conventional view.

The Tip of the Iceberg

These costs are imposed on society as a whole. In everyday life, people, companies and governments are often unaware of the impact that nutritional decisions in particular can have on whether agricultural and food systems are sustainable or not. The costs usually revealed at the supermarket checkout are just the tip of the iceberg.

The recently published FAO report "The State of Food and Agriculture" 2023, or SOFA for short, takes a closer look at these "true costs". Under the heading "Revealing the True Cost of Food to Transform Agrifood Systems", the SOFA report looks at true cost accounting (TCA), i.e. the calculation of the hidden effects of agricultural and food systems – whether positive or negative. These are real costs that have to be paid sooner or later, but which are not included in the prevailing system recording the effects of our economic activity.

In an initial assessment at national level for 154 countries, the FAO estimates the global hidden costs to be at least 10 trillion dollars per year. This is a huge figure, which becomes all the more relevant when you consider that the market value of all food consumed worldwide is estimated at 9 trillion dollars. This means that we have to spend even more than this amount to pay for the side effects of our food production and consumption. These hidden costs arise along the entire food value chain and are not currently borne by those who cause them. Ultimately, they must be shouldered by society, especially by people in the Global South and future generations. In the SOFA report, the FAO therefore emphasizes the urgent need to take these hidden costs into account when shaping the food transition.

Figure 1: Wertschöpfung und schädliche Nebenwirkungen

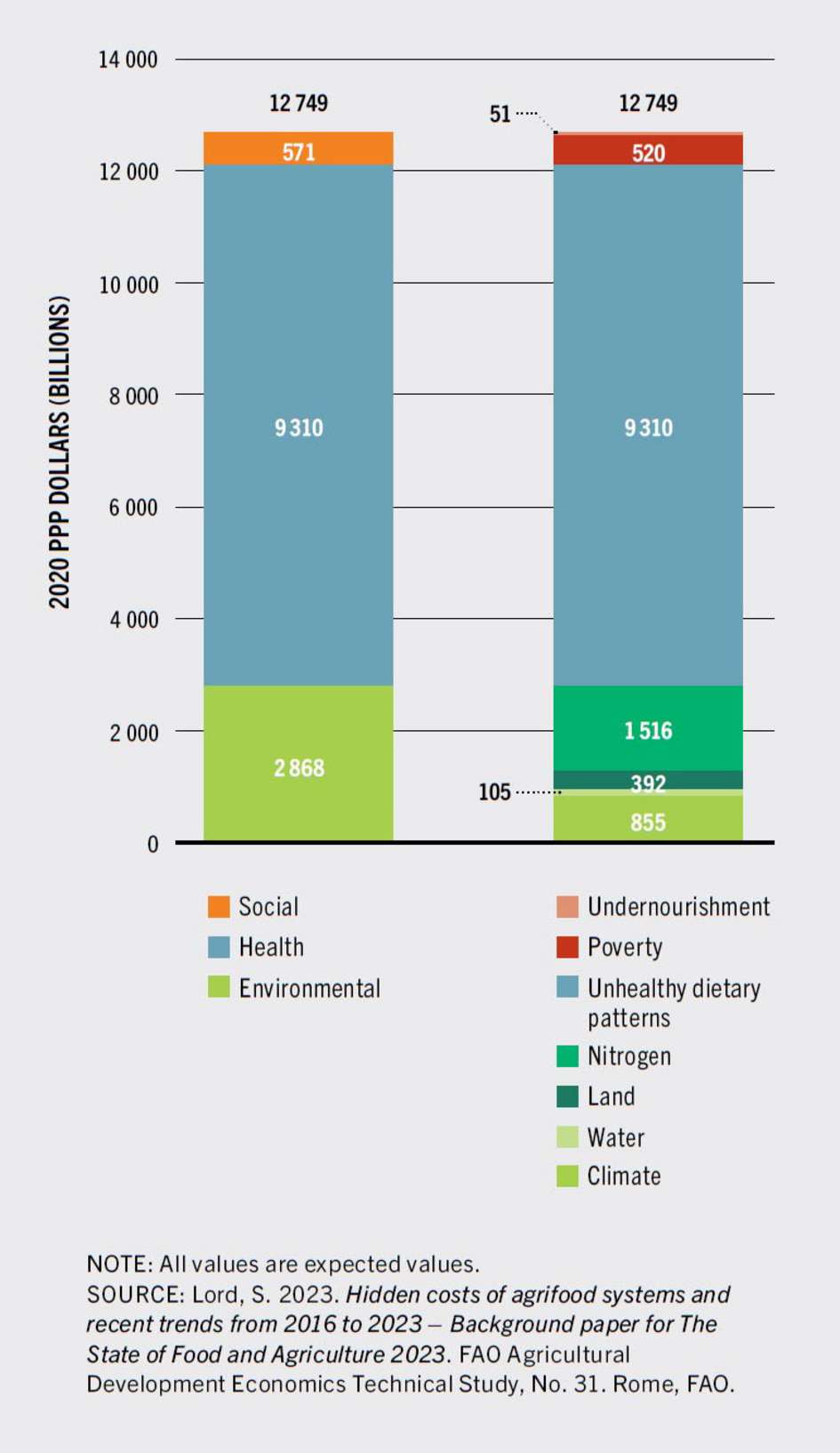

Hidden costs are made up of environmental, health and social costs. Environmental costs caused by agrofood systems account for around a fifth of hidden costs. However, with a projected value of almost 2.9 trillion dollars a year (adjusted for purchasing power in 2020), these costs are probably underestimated according to the FAO. Nitrogen emissions account for more than half of the hidden environmental costs, followed by greenhouse gases, land use change and water consumption. In Germany alone, the hidden environmental costs of the food system amount to around 30 billion dollars per year – that is almost one and a half times the output of German agriculture (22.2 billion dollars gross in 2020).

Health costs account for the largest share by far. According to the report, more than 70 percent are caused by unhealthy eating habits. These costs vary greatly from country to country and are highest in high- and middle-income countries. Here in Germany, people suffer from diseases caused by overeating and faulty diets. We eat too much, too much fat, too much sugar and too much industrially processed food and meat. Dietary habits are linked to the development of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer. Treating them costs a lot of money – which is not only paid by the healthcare system. Loss of productivity due to diet-related diseases has a negative impact on economic performance. Both unhealthy dietary habits and malnutrition lead to absenteeism.

Figure 2: Share of Hidden Costs

However, while the hidden costs of unhealthy eating habits in industrialized countries are assigned to the health sector, the report assigns the costs of malnutrition (and poverty) to the social sector. According to the report, the social impact accounts for the smallest proportion of hidden costs, namely four percent. However, social costs are particularly high in developing countries due to the effects of poverty and malnutrition.

Hidden Costs affect Poor Countries more Severely

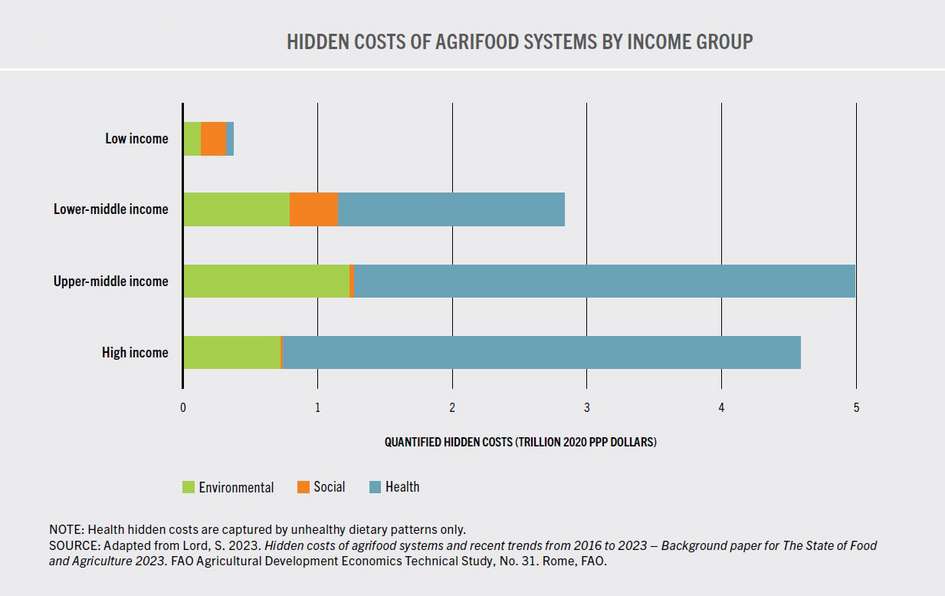

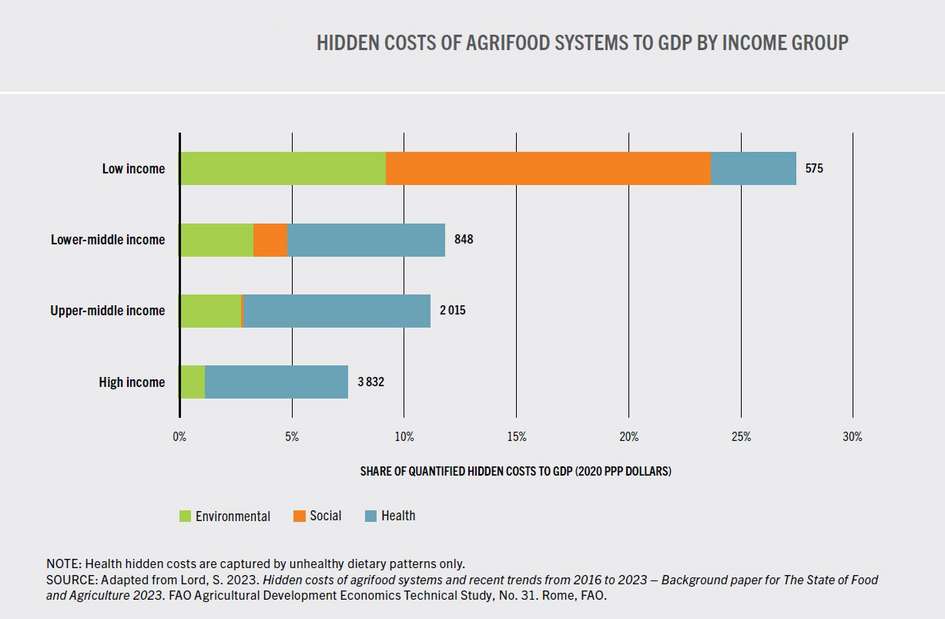

The global summary of the hidden costs of agrifood systems hides considerable differences in income between countries, which play a key role in reducing these costs (see Figure 3). In absolute terms, the majority of these costs are incurred in middle- and high-income countries. Nonetheless, in relative terms, hidden costs represent a greater burden for low-income countries. As a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP), their burden on national economies becomes clear. On average, the quantified hidden costs correspond to just under 10 percent of GDP globally. In low-income countries, however, this proportion is much higher, averaging 27%. In comparison, it is around 11% of GDP in middle-income and 8% in high-income countries.

This is due to the way food is produced, which differs significantly between industrialized and developing countries. In industrialized countries, the economy – and agriculture in particular – is capital-intensive, whereas in developing countries it is labor-intensive. As a result, the GDP share of labor and agriculture is higher in poorer countries. At the same time, hungry and malnourished people are less productive: therefore, poor nutrition - expressed here as a hidden cost factor of substandard nutrition and hunger – is not only an individual and humanitarian problem, but also an obstacle to economic and social development.

Figure 3: Hidden Costs according to Country Income Level

The FAO findings show that rich countries above all need to work on transforming their dietary habits. Reducing meat consumption has the greatest potential to drastically reduce greenhouse gases and land use while at the same time achieving positive health effects. Clearly, the Western food system should under no circumstances be exported to other regions as a model or ideal. For developing countries, it is confirmed that the fight against poverty and hunger must be a central pillar of the development process in order to reduce hidden costs in the long term.

How can hidden food costs be reduced?

The True Cost Accounting (TCA) model aims to analyse and quantify the impact of methods of production and consumption on the environment and society in order to reveal the total costs and benefits of a product or service. As an interdisciplinary approach, TCA analyses food systems holistically and takes into account the links between economic, environmental, health and social systems.

The FAO emphasizes the potential of TCA as a catalyst for change – a tool to uncover hidden costs and thus inform policy makers and improve the output of agricultural and food systems. The new national-level estimates of the SOFA 2023 report aim to identify points of departure for prioritizing interventions and investments, while the SOFA 2024 report will provide more detailed case studies for value chains and countries and corresponding policy recommendations.

In general, the aim is not to transfer the burden of the costs of our unsustainable food system onto society. Given the political will, government policy can institute changes based on TCA analyses that reduce the hidden cost of food and lower the cost to society: possible measures include regulation or taxation of food, changes to subsidies or, in an optimal scenario, a mix of measures sharing costs between producers and consumers. For example, the World Bank estimates that up to 600 billion US dollars are spent annually on subsidizing agriculture, the reallocation of which could make a major contribution to the reduction of hidden costs.

A necessary measure should also be to change corporate accounting so that it does not ignore hidden costs. Instead, risks relating to natural, social and human capital should be included in regular reporting while their improvement should have a positive effect on the company balance sheet.

However, companies need not wait for political measures. They can take the initiative and become leaders in transformation through TCA. TCA offers the private sector a basis for providing information about the true costs of products, changing the way food is produced so that there are fewer hidden costs and communicating its sustainability and future viability to investors. This is already possible even today on a voluntary basis. In the background paper "The role of true cost accounting in guiding agrifood businesses and investments towards sustainability", produced by TMG Research, companies that are taking the lead in TCA in various applications are presented.

Working together for a sustainable economic revolution

TCA creates a framework for a comprehensive reassessment of food systems and business models. However, effective implementation requires a high level of cross-sector expertise. Due to the interdisciplinary nature and novelty of the approach, its further development and practical implementation requires a broad network of contributors. The aim is to combine research and possible solutions from various perspectives and fields in order to cooperate on scaling up this sustainable economic approach.

In order to reach this goal, TMG Research and partners from academia (Regionalwert Research, Nuremberg Institute of Technology) and civil society (Misereor) have launched the TCA Alliance. Here, interest groups from business, politics, science and civil society, provided with financial support, are to further develop and test the TCA approach and make it applicable in practice. Standardized methods and tools play a decisive role in making the workings of the economy more sustainable through TCA. A network of cooperation can also set research priorities. The TCA Alliance thus sees itself as start up for developing concrete plans for the future.