Global Agricultural Trade: Robust Safety Net to Reduce the Risk of Hunger

Even in times of crisis, competitive international agricultural trade is proving to be a robust aid to food security – regional supply shortages resulting from the war in Ukraine have been overcome.

Hunger, wars, global warming – phenomena and risks that are closely linked – are the scourge of humanity, especially in the Global South. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO et al., 2022) estimates that the number of people affected by hunger has recently increased by about 150 million, probably in relation to the COVID-19 crisis. South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are most affected by hunger and risks to nutrition. At the same time, 700 million people, or nearly 10 percent of the world's population, are still expected to be undernourished in 2030: putting UN development goals further out of reach. Looking at the World Hunger Index, it becomes clear that the continuous decline in hunger has come to a virtual standstill over the past two decades.

As a result of the war in Ukraine, the food situation is likely to have worsened, particularly in poor countries of the Global South. Global market prices for agricultural commodities such as cereals and vegetable oils, which since the fall of 2021 had already reached the high price levels of the 2007/2008 and 2010/2011 food crises, rose even further by May/June 2022. Wheat importers in the MENA region and in regions of sub-Saharan Africa, where demand boomed, were particularly affected. Russia and Ukraine had been their main suppliers. Bottlenecks in supply from the Black Sea region, coupled with high prices, put additional pressure on the already critical food situation in these regions.

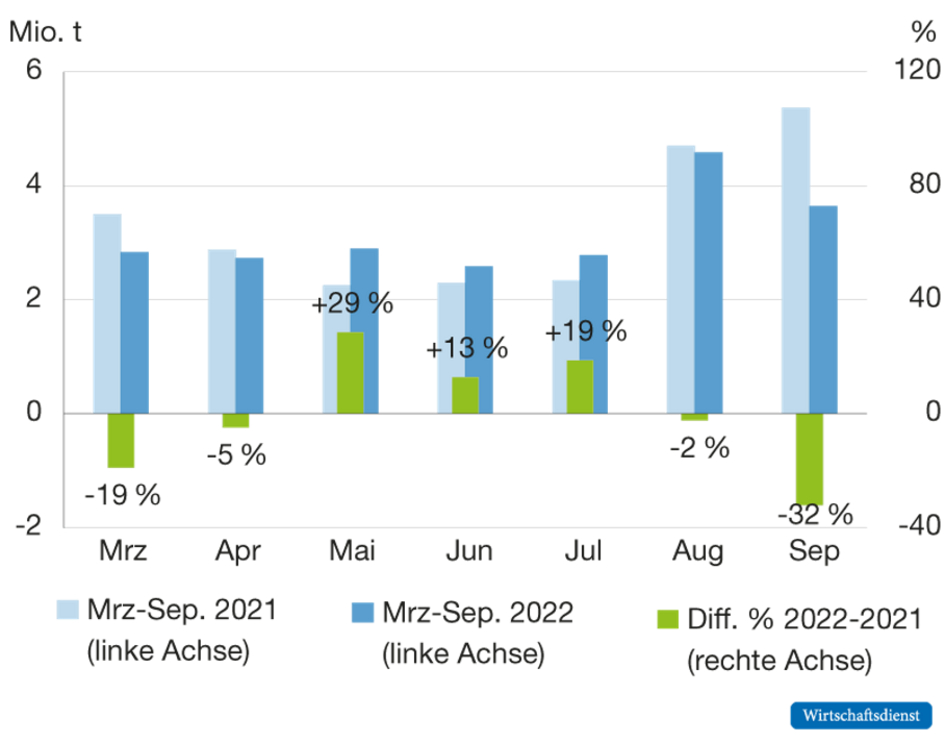

However, as expected, the situation had already eased a few months after the start of the war (Glauben, 2023; Vos et al., 2023). Shortfalls in supplies to Africa from Ukraine, for example of wheat, one of the most important staple foods, were largely offset by supplies from other countries, such as France, India, and Australia (Glauben et al., 2022; Götz and Svanizde, 2023). In the first six months after the start of the war, the amount of wheat shipped to Africa was already almost equal to that of the same period (March to September) in the pre-war year 2021 (Eurostat, 2022; UN Comtrade, 2022; Refinitv-Eikon, 2022, see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wheat exports to Africa

As a result of the markets calming down in the 2022/2023 marketing year, not least as a result of good harvests and increased exports from Canada, the EU, Australia and Russia, wheat prices on international marketplaces such as the Paris commodities futures exchange EURONEXT have fallen significantly, despite noticeably lower supplies from Ukraine as well as drought-related reductions from Argentina (Vos et al., 2023): from a peak of 450 EUR per ton of wheat in March 2022 to 230 EUR per ton in May 2023, i.e. by almost 50 percent and thus to pre-war levels. Insecurity regarding developments in Ukraine was already reflected in these prices.

These recent developments indicate once again that international agricultural trade based on competitive markets is proving to be a suitable strategy for dealing with risks resulting from regional supply bottlenecks – be they related to weather, crises or political developments. In sum: The "safety net of global agricultural markets" is proving to be robust in the fighting hunger.

Growing global agricultural trade meets rising demand for food in the Global South

To understand the dynamics and adaptability of international agricultural trade, a historical perspective is useful. Not least since the founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO), international agricultural trade has grown considerably in importance. In 30 years, global agricultural exports have more than tripled from $450 billion to $1.5 trillion (in nominal terms), at an average annual rate of growth of about five percent (FAO, 2022). In the process, the growth in trade even exceeded that of global production, while at the same time real prices fell in the long term, albeit subject to considerable fluctuation.

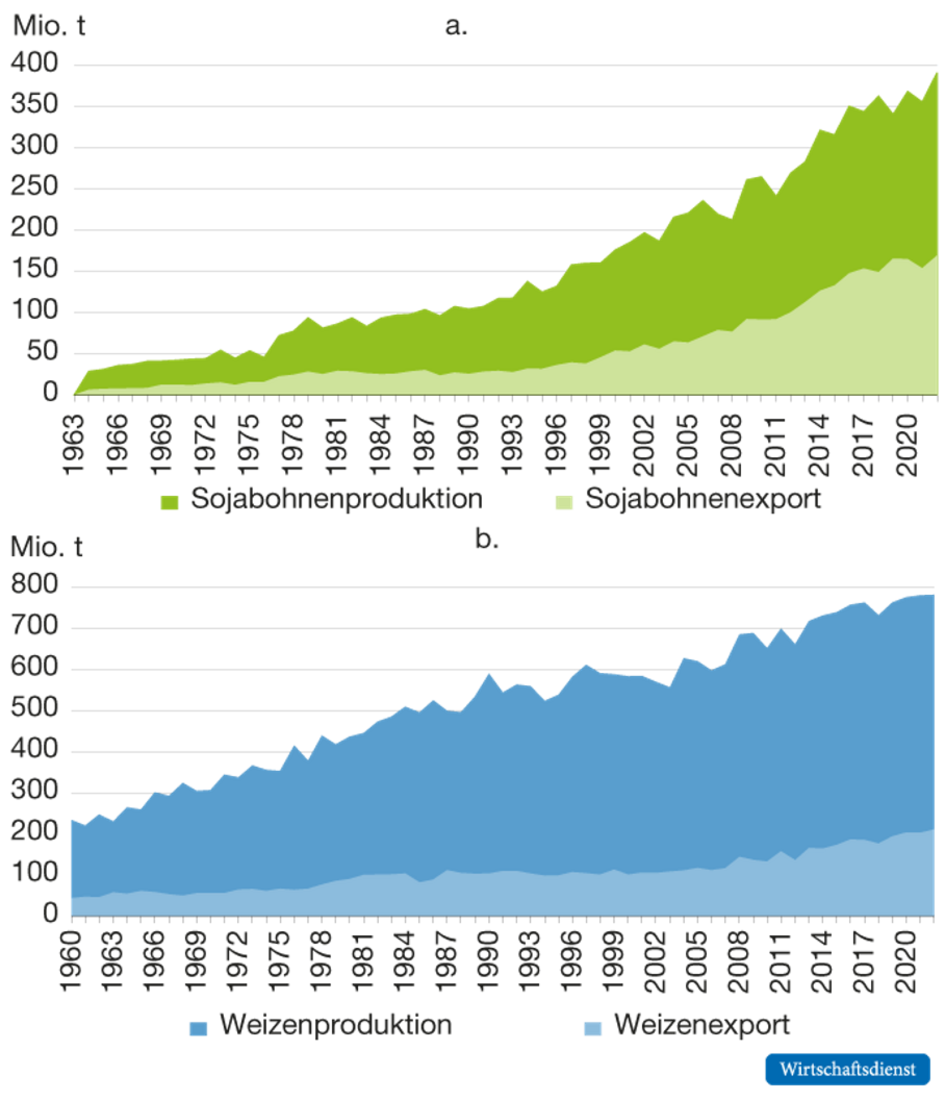

Thus, for the most important agricultural commodities, trade as a share of total production increased. It increased from 18 percent to 27 percent for wheat, from 25 percent to 44 percent for soybeans, and from 5 percent to 11 percent for rice, while remaining roughly constant for corn (USDA, 2023). A steady increase in trade, as well as production, of key agricultural commodities can be observed since the middle of the last century. This may have contributed to a reduction in the risk of hunger. At that time, about half of the world's population was affected by hunger; today, the figure is just under ten percent. Wheat trade, for example, has increased fivefold since 1960, while global production has quadrupled.

Figure 2: Production and export of soybeans (a) and wheat (b)

As is well known, high population growth, especially in Africa, and more recently growth in incomes in Asia have boosted import demand. On the supply side, growth in production and trade is the result of technological advances in production and distribution as well as of the opening of international markets, i.e. of the steady, if not always trouble-free, expansion of a largely open multilateral (agricultural) trade system. Agricultural trade has thus made a significant contribution to food supply and consequently to the reduction of hunger risks in the Global South.

Currently, Europe and the Americas, for example, are net exporters of agricultural goods and thus of vital nutrients, while Africa and Asia are net importers (OECD/FAO, 2022). For example, North Africa and the Middle East (MENA) import nearly 70 percent of their domestic nutrient requirements. In most other regions, the share of imports of domestic nutrient requirements fluctuates at around 20 to 30 percent. All in all, it is clear that without trade, the extent of hunger worldwide would be far more serious.

Against this background, many observers expect the importance of international trade to meet rising global food demand will continue to increase. Climate change, with its accompanying extreme weather events, and violent conflict in many poorer regions of the world are expected to exacerbate food risks in the Global South, and this often cannot be mitigated through local adaptation (Hornidge and Brüntrup, 2022). About 60 percent of the world's people affected by hunger live in areas of armed conflict where agricultural systems are considered fragile and unstable. Africa, where nearly 70 percent of the population is affected by food crises, also records the highest incidence of conflict.

Global agricultural trade proves reliable and flexible

Clearly, the move toward a largely competitive and open global (agricultural) trading system has paid off. It is making a not inconsiderable contribution to reducing food insecurity. This is a remarkable achievement, not least in the face of recurring and quite severe market disruptions, for example through temporary or ad hoc interventions such as government-imposed export/import restrictions, sanctions or bureaucratic excesses of centrally planned economies. In 2022 alone, restrictions were imposed by around 30 countries. They affected up to 15 percent of agricultural trade (Laborde and Mamun, 2022). In the first Corona year, about 20 countries, including Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Turkey and Vietnam, had introduced restrictions to agricultural trade that reduced calorie availability in some North African countries by up to 40 percent, at least in the short term (Laborde and Mamun, 2022).

Notwithstanding such market disruptions and politically motivated market interventions, the largely competitive agricultural commodity trade has proven to be quite robust over the decades, to a large extent closing (constantly) changing gaps in supply between producing and consuming regions. The WTO and its predecessors, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), also played an important role: they kept threats to open trade from political powerplay in check, promoted the free movement of goods and enabled the settlement of disputes.

This is impressively illustrated by the international wheat market. The market is characterized by considerable growth and has in its core has always been characterized by a multipolar structure, i.e. quite a large number of supply and demand regions.

Since the middle of the last century, international wheat trade has been characterized by quite pronounced diversity and adaptability in the ranking of supply and demand regions. North America and Australia have been among the most important exporters since the 1960s. Since the 1980s, Europe has gained in importance. Since the early 2000s, the Black Sea region has gained momentum to become a key supplier of the most important staple foods. In contrast, on the import side the territory of the former Soviet Union, including the Black Sea region, was among the major destinations of wheat exports from the 1970s to as late as the 1990s, while Europe became a net exporter. Today, populous regions in Africa and Asia, including China in particular, are driving import demand.

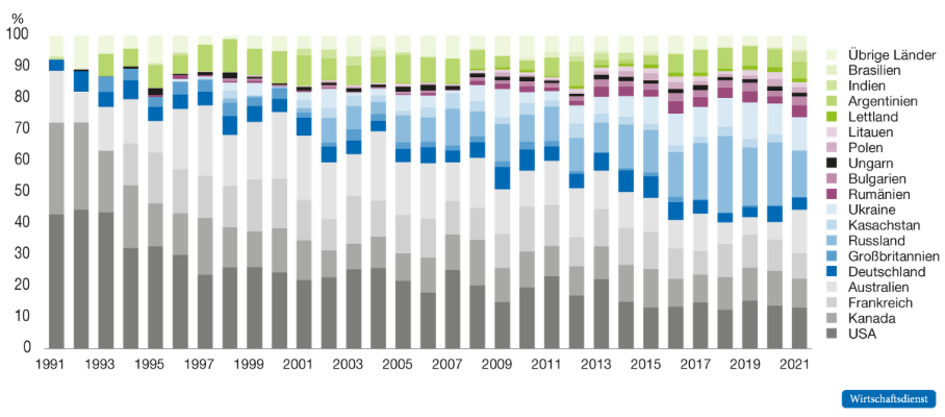

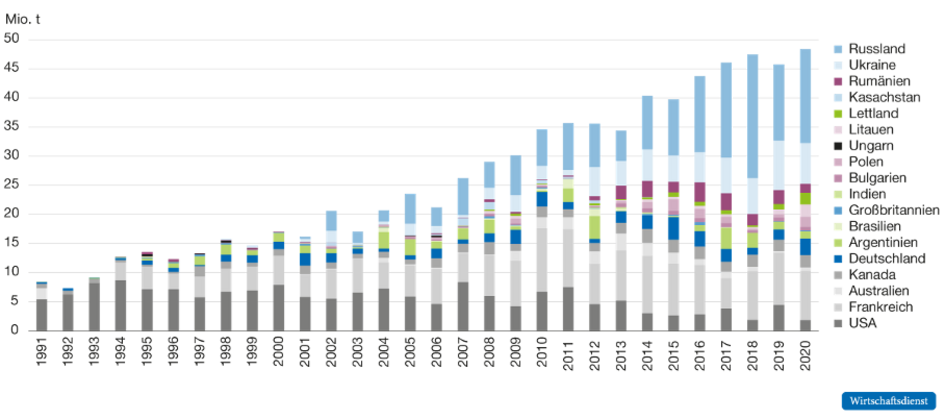

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the shift in the weighting of exporting nations in their importance, on the one hand, for global markets and, on the other, for wheat supplies to Africa. It is clear the former centrally planned economies of Eastern Europe, especially Ukraine and Russia, have gained massively in relative importance since the early 2000s in supplying the population suffering from hunger in in AFrica, while in comparison almost all other important export nations, such as North America, have lost importance.

Figure 3: Wheat exports by main exporters

Figure 4: Wheat exports to Africa

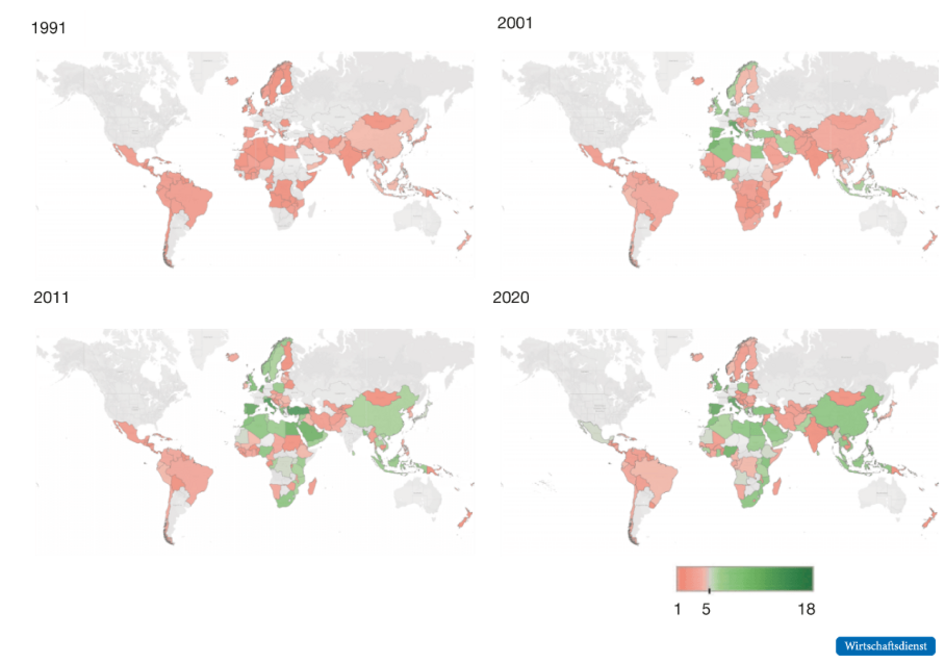

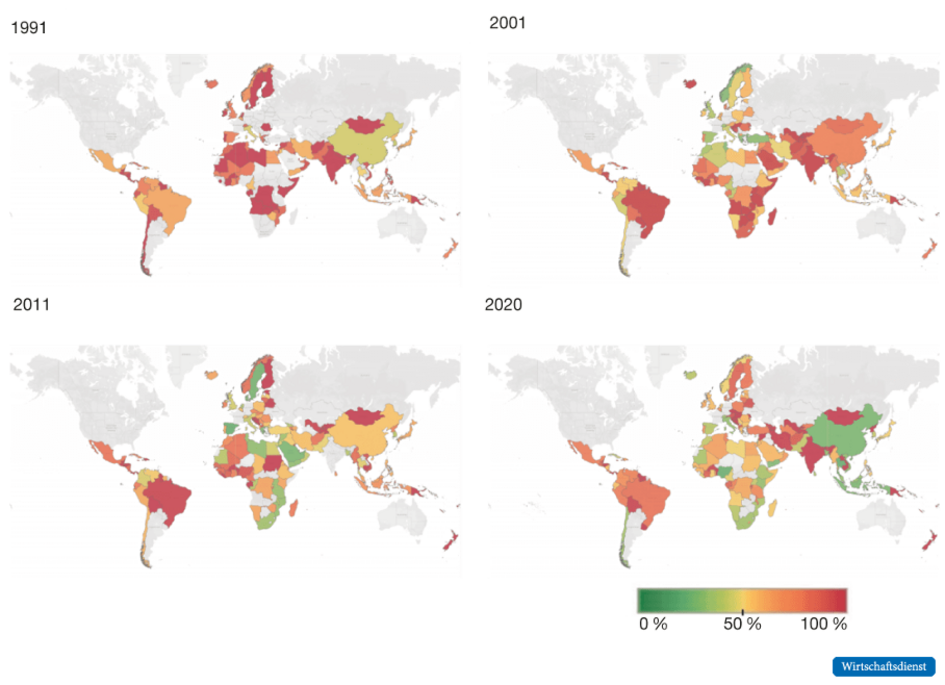

At the same time, the massive growth of global trade in wheat, which was in effect not restricted to established markets, led to a remarkable and continuous diversification of regional import and export structures. The market became less constricted. This is likely to have contributed to increased resilience of trade and supply. As can be seen in Figures 5 and 6, the number of supplier countries per importing country has increased noticeably in over period of 30 years: from 1-5 countries in 1991 to 5-18 nations in 2020. This is particularly true for Africa and Asia. As a result, the share of the major wheat supplier of importing countries has also decreased, from about 45 to 20 percent on average. In comparison, South America and Central Asia few signs of greater diversification of trading partners can be found in. It is certainly interesting to note that the most substantial (annual) bilateral trade flow has fallen from 12 to 4 percent of total trade in just under 20 years.

Figure 5: Number of wheat trading partners, average per importing country, selected years 1991 to 2020.

Abbildung 6: Anteil des größten Weizenlieferanten im Zielland (in %, ausgewählte Jahre 1991-2020)

What is th conclusion? All in all, these observations point to a fairly reliable and functioning system of international wheat trade that is able to match supply from regions with a surplus to import demand from regions with a deficit through a market driven "combination" of well-established trade relations and flexible adjustments.

Recent econometric analyses of the stability of the global wheat market from 2001 to 2021 support this view (Jaghdani et al., 2023). According to this analysis, at the end of the period under review (2021), both "old" and "new" players had varying probabilities of stability of their wheat exports. This suggests a good "mix" of trade relations. The continuity of supply by Canada, Australia, the USA and Russia is estimated to be comparatively high, that by Romania, Ukraine and Germany medium and that by Kazakhstan and Argentina lower. Events in 2022/2023, such as the war in Ukraine or the escalating trade conflict between the USA and China have not yet been taken into account.

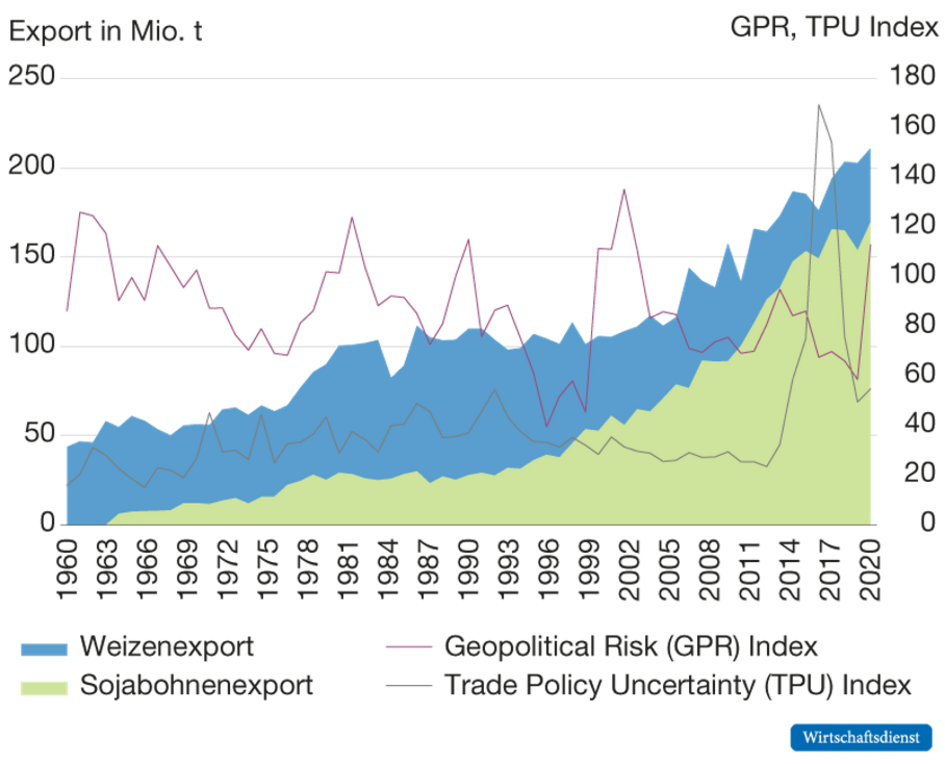

When the long-term trends in both international wheat and soybean trade over the past 60 years are juxtaposed with two measures of geopolitical risk and trade uncertainty that reflect potential risks to trade patterns, trade, as shown in Figure 7, proves to be quite robust overall.

Figure 7: Geopolitical risk, trade policy uncertainty, and wheat and soybean trade.

Black Swan: Open agricultural trade is not the problem, it is part of the solution

Global trade, including agricultural trade, is in danger of getting into massive trouble – which could result in significant threats to the security of supply for the poor and for people affected by hunger in the Global South. Geopolitical activism, power politics by major actors, systemic competition, conflict and war threaten to divide the world into (new) blocs. Isolation, centrally planned economies and efforts at achieving autonomy appear to be gaining favor. This goes hand in hand with climate change and global warming.

The situation is reminiscent of a "black swan", a simplified term for a situation in which all known factors do not allow conclusions to be drawn about future risks and the actors are unaware that the unexpected could occur (Taleb, 2007). WTO global trade rules appear to be in danger of becoming irrelevant. These have traditionally focused on "shallow integration". In particular, they emphasize the reduction of trade barriers such as tariffs, subsidies or discriminatory protective and administrative regulations.

At present, various sides are increasingly arguing that social values as well as aspects of the security of supply and of external security should be given greater weight when it comes to shaping international (agricultural) business relations. This, it is argued, would reduce dependencies on nations that are not "like-minded”. Under the heading of "sovereignty", calls are made for isolation and (micro-)management of international marketplaces. "Command economists" and self-designated geopolitical "strategists" are raising their voices, calling for state-imposed intervention in global trade which is said to promote greater regional diversification in trade relations and to lead to a higher degree of self-sufficiency. Calls for the adherence to a shared value system as a prerequisite for transnational trade relations are also becoming louder.

Ill-conceived ideas

The desire for security of supply may be understandable, but such proposals are questionable and ill-conceived. They may well result from the hope that autonomy or central control of international (agricultural) trade could be the recipe for reducing supply risks in future (Bentley et al., 2022). However, the opposite is to be feared. In effect, one would veer from the well-proven principles of a market economy to some kind of (partial) global command economy. In agricultural trade, this could lead to shortages in the Global North and the collapse of food supplies in the Global South. Politically motivated agricultural trade structures designed on the drawing board will not (be able to) replace the market. They will lead to less, not more security of supply.

It is a truism that the manipulations of a command economy weaken or even render ineffective the market as a well-oiled, well-proven coordinator of agricultural trade relations and its functions of regulating supply, price and innovation. There is less chance for exploiting relative cost advantages, if at all. Regional supply bottlenecks can no longer be efficiently overcome by supplies from other regions. Prices increase drastically, provided goods are still available, and the "safety net of global agricultural trade" is weakened.

The observations of wheat markets presented above indicate clearly that largely open agricultural trade is proving robust and adaptable to shocks and even to massively changed conditions. It “automatically” led to a market-driven diversification of sources of supply and procurement, taking into account risk management. What bureaucratic dirigiste institution could control such complex systems in manner that would even come close to such efficiency and precision?

Even more absurd is the appeal to vague "geopolitical considerations" that demand that (agricultural) trade should be conducted only with trading nations that conform to certain values, such as having a (purely) democratic system of state and society. If (agricultural) trade is subjected to such a normative decree, hardly any trading partners remain, especially in the Global South. Such ideas are hardly feasible in reality without creating a command-economic, bureaucratic "monster" - and would predictably create a form of agricultural trade that would that lead to a drastic aggravation of hunger in the Global South. The cost of such "planning exercises" would largely be borne by the poor in the Global South.

Of course, trade alone is not sufficient for reducing the risk of hunger in vulnerable regions. Development processes at the local, regional and global levels are crucial and require time and patience. Hunger or poverty cannot be "eliminated by transformation" at the drawing board. Promising innovative approaches to make food production more sustainable, adapted to climate change and resource-efficient at a local level can also face up to periodic droughts and extreme weather and environmental demands (Kray et al., 2022). Investment in research, education and advisory services is an important prerequisite for the development of modern agricultural systems. In this area, an international exchange of ideas is crucial for regional development processes.

Editor's note: This article is an abridged version of the analysis of the same name that appeared in Wirtschaftsdienst, Volume 2023, Issue 7, with the kind permission of the authors.

Literature

Bentley, A. R., J. Donovan, K. Sonder, F. Baudron, J. M. Lewis, R. Voss, P. Rutsaert, N. Poole, S. Kamoun, D. G. O. Saunders, D. Hodson, D. P. Hughes, C. Negra, M. I. Ibba, S. Snapp, T. S. Sida, M. Jaleta, K. Tesfaye, I. Becker-Reshe und B. Govaerts (2022), Near- to long-term measures to stabilize global wheat supplies and food security, Nature Food, 3, 483-486.

Caldara, D. and M. Iacoviello (2022), Measuring Geopolitical Risk, American Economic Review, April, 112(4), 1194–1225, https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm (26. June 2023).

Caldara, D., M. Iacoviello, P. Molligo, A. Prestipino and A. Raffo (2020), The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty, Journal of Monetary Economics, 109, 38-59, https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/tpu.htm (12. June 2023).

Eurostat (2022), The statistical office of the European Union, European Commission.

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (ed.) (2022), The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2022, The geography of food and agricultural trade: Policy approaches for sustainable development, FAO.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2022), The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022, Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable, FAO.

FSIN – Food Security Information Network (2022), 2022 Global report on food crises. Food and Agriculture Organization.

Glauben, T., M. Svanidze, L. Götz, S. Prehn, T. Jamali Jaghdani, I. Duric and L. Kuhn (2022), The war in Ukraine, agricultural trade and risks to global food security, Intereconomics – Review of European Economic Policy, 57(3), 157-163, https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2022/number/3/article/the-war-in-ukraine-agricultural-trade-and-risks-to-global-food-security.html (12. June 2023).

Glauben, T. (2023), Der Ukraine-Krieg, der Welthandel und der Hunger im Globalen Süden, Politikum, 1.

Götz, L. and M. Svanidze (2023), Getreidehandel und Exportbeschränkungen während des Ukrainekriegs, Wirtschaftsdienst, 103(13), 37-41, https://www.wirtschaftsdienst.eu/inhalt/jahr/2023/heft/13/beitrag/getreidehandel-und-exportbeschraenkungen-waehrend-des-ukrainekriegs.html (12. June 2023).

Hornidge, A.-K. and M. Brüntrup (2022), Afrikas anschwellende Hungerkrise: Was können G7 und G20 dagegen tun?, Welternährung Das Fachjournal der Welthungerhilfe, Entwicklungspolitik & Agenda 2030, 10, https://www.welthungerhilfe.de/welternaehrung/rubriken/entwicklungspolitik-agenda-2030/g20-wie-vertragen-sich-industrie-und-schwellenlaender (12. June 2023).

Jaghdani, J. T., T. Glauben, S. Prehn, L. Götz and M. Svanidze (2023), The stability of global wheat trade – a duration approach (unpublished manuscript, accepted for the XVII EAAE Congress in Rennes 2023), IAMO.

Kray, H., T. Syed and A. C. C. Gomez (2022), Healthy humans, animals, ecosystems – One Health in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2. June, World Bank Blogs, hhttps://blogs.worldbank.org/nasikiliza/healthy-humans-animals-ecosystems-one-health-eastern-and-southern-africa (12. June 2023).

Laborde D. D. and A. Mamun (2022), Documentation for Food and Fertilizers Export Restriction Tracker: Tracking export policy responses affecting global food markets during crisis. Food and Fertilizer Trade Policy Tracker, Working Paper, 2, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

OECD and FAO (2022), OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022-2031, OECD Publishing.

Pies, I., M. G. Will, T. Glauben and S. Prehn (2015), The Ethics of Financial Speculation in Futures Markets, 771-804, in A. G. Malliaris and W. T. Zemba (Hrsg.), The World Scientific Handbook of Futures Markets, World Scientific Publishing.

Refinitv-Eikon (2022), Reuters database of port shipping data, eikon.refinitiv.com.

Taleb, N. N. (2007), The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Impropable, Penguin Books.

UN Comtrade (2022), The United Nations trade database, comtradeplus.un.org.

USDA – United States Department of Agriculture (2023), USDA Production, Supply and Distribution database, apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app (12. June 2023).

Vos, R., J. Glauber and D. Laborde (2023), Is food price inflation really subsiding?, IFPRI Blog: Issue Post.