Migration in Southern Africa - Openness is Overshadowed by Xenophobia

South Africa's migration policy is at a turning point. It has to balance the need for qualified immigrants against high unemployment and poverty - and protect both refugees and asylum seekers.

South Africa has a long history of attracting migrants from neighbouring countries to work in the mines, on farms or as domestic workers. Comparatively open policies instituted after the end of Apartheid in 1994 have become significantly more restrictive in recent years. Economic and political tensions have led to violent outbreaks of xenophobia. Migration has become a contentious issue ahead of national elections in 2024.

According to the latest census data, South Africa is home to 2.4 million international migrants which constitutes 4 per cent of its total population of 62 million people. This is a slight increase from the 2.1 million recorded in the 2011 census. However, it falls below the official estimate of 2.9 million for the period preceding the latest census. The number of immigrants, particularly from neighbouring countries can be difficult to ascertain due to the presence of large numbers of irregular migrants.

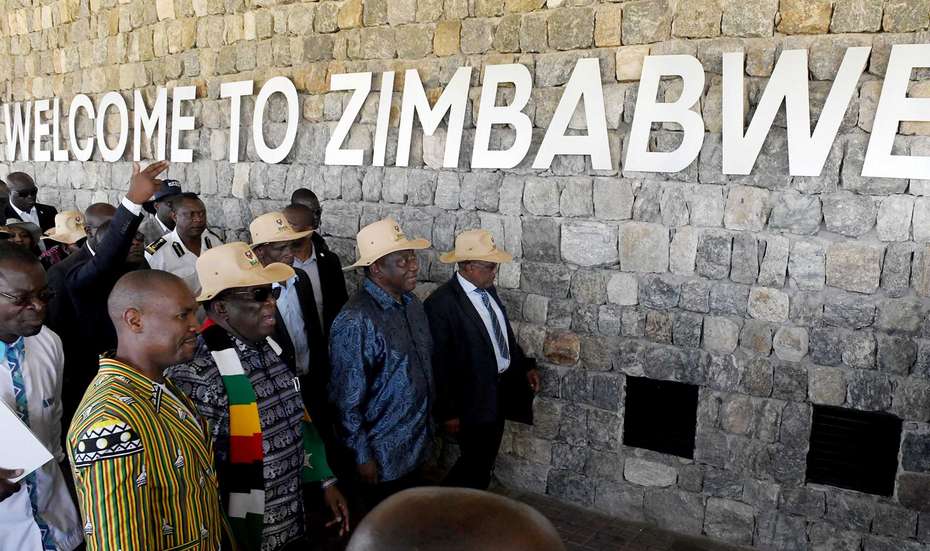

According to the 2022 census, the top four sending countries are Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, and Lesotho which are located within the southern African region and – except for Malawi – share land borders with South Africa. The neighbouring countries which are part of the 16-member regional body, the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), contribute a combined 80 per cent of the total number of international migrants in South Africa. This is a significant increase from the 68 per cent recorded in the 2011 census. The presence of migrants from neighbouring countries is unsurprising, given the fact that most international migrants tend to stay within their regions rather than migrate to distant countries. Within South Africa, migrants are not evenly distributed, with the majority living in the Gauteng province which is the economic hub of the country and comprises three metropolitan areas, namely, Johannesburg, Tshwane (Pretoria) and Ekurhuleni.

Within the Southern African region, the movement of people from neighbouring countries is aided by the long history of migration to South Africa dating back to the discovery of commercially viable gold deposits in the Witwatersrand basin in 1886 (Moyo 2020). This inaugurated the contract migrant labour system through which labourers were recruited from neighbouring countries to satisfy the demand for cheap labour in the South African gold mines (Wilson 1976).

Some academic writers have noted that the contract labour system that channeled labourers to the mines and commercial farms existed alongside another system of clandestine and irregular migration which was actively encouraged by the apartheid colonial government of South Africa (see for instance, Musoni 2020). Thus, the migration routes from neighbouring countries to South Africa have been in existence for over a century and have facilitated present day patterns of movement in the region.

Due to the configuration of the colonial southern African economy, South Africa grew disproportionately in comparison to its neighbours and has continued to sustain this advantage as seen in the size of its GDP. It has a GDP of 405.27 billion US dollars which is almost equivalent to the combined GDP of all the other 15 SADC countries.

While the earlier forms of movement were driven by the demand for labour in the South African mines and farms, the current patterns are more variegated. In addition to the neighbouring countries, South Africa also attracts migrants from the rest of the African continent, the Indian sub-continent, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Some migrate in search of economic opportunities and others in search of sanctuary as they flee wars and other socio-political disturbances in their countries of origin. South Africa currently hosts just over 250’000 refugees and asylum seekers and the main source countries include the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), South Sudan, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe.

Where do migrants work?

Amongst other forms of work, migrants from neighbouring countries find work on South African commercial farms, particularly closer to the land borders. There is considerable scholarly research that has focused on the historical presence of Zimbabwean farm workers in the Limpopo province (Hall et al, 2013), Lesotho farm workers in the Free State province (Johnston, 2007) and Mozambican farm workers in the Mpumalanga province (Mathers 2000). Farm laborers have been characterized as both permanent and seasonal and at times transiting through the farms.

In the case of Zimbabweans, the seasonal farm workers mainly consist of labourers from the border town of Beitbridge who cross into South Africa when there is demand for farm labour, particularly during harvests (Bolt 2017). There are also those that make pit-stops in the farming areas on their way to other parts of South Africa, mainly Johannesburg and Pretoria. They stop to raise money for further travel or to re-stablish contact with their relatives in Gauteng. In addition to farm work, many undocumented migrants from neighbouring countries find work as domestic workers in the major cities such as Johannesburg (Zack et al, 2019).

How has South Africa responded to the migration?

South Africa’s response to the arrival of migrants and refugees has been varied and inconsistent since the end of Apartheid and the dawn of democracy in 1994. There are two pieces of legislation that govern migration into the country, namely, the Refugees Act of 1998 and the Immigration Act of 2002. The 1998 Refugees Act gives refugees and asylum seekers similar rights to citizens, apart from the right to vote, though its implementation is often subject to criticism. The 2002 Immigration Act places emphasis on attracting skilled migrants and does not make sufficient provision for unskilled and semi-skilled immigration to South Africa (Moyo and Zanker 2022).

With limited avenues for legal immigration, many unskilled migrants resort to staying undocumented or using the asylum system as a surrogate immigration channel – which has resulted in bureaucratic inefficiencies and overloading of the system. For example, during the height of the Zimbabwean crisis in 2008 and 2009, there were over 140’000 new applications for asylum per annum from Zimbabweans alone. Zimbabwe has experienced a period of protracted political and economic instability since the late 1990s and reached unprecedented levels of hyperinflation, peaking at 89.7 sextillion (10^21) percent in November 2008. This was the second highest level of inflation recorded in history after Hungary in 1946, further driving thousands of Zimbabweans into neighbouring countries.

Thus, South Africa grapples with a massive problem of undocumented immigrants from neighbouring countries. For a long time, the country relied on the arrest and deportation of irregular migrants – which proved costly and ineffective, especially where cross border migrants are concerned. For instance, during the peak of the Zimbabwean crisis around 2008 and 2009, South Africa reached figures of over 200’000 deportations per year but most of the deported immigrants found their way back into the country almost immediately.

Progressive Policy direction 2010 – 2021

In 2009 South Africa announced the Dispensation for Zimbabweans Project (DZP) which aimed to regularize undocumented Zimbabweans, offer amnesty to those with fraudulent South African identity documents and allow those on the asylum system to apply for the special permits. The announcement of the DZP was accompanied by a moratorium halting the deportation of Zimbabweans. The special permits were initially issued for a period of four years and were renewed in 2014 for three years and again in 2017 for another four years.

The special permits model was extended to Angolan refugees who chose to remain in South Africa after the cessation of their refugee status in 2013. In 2015 a similar programme was initiated for citizens of Lesotho to regularize their documentation status in South Africa.

The implementation of the special permits informed some proposals in the government’s 2017 White Paper on International Migration (WPIM 2017) which proposed a SADC visa to cater for unskilled and semi-skilled economic migrants from the region. This was described as recognizing the long history of immigration from the region and seeking to provide an avenue for unskilled migrants who ordinarily would not qualify for visas in terms of the Immigration Act of 2002.

The progressive policy direction seen in the decade of the special permits however came to an abrupt halt in November 2021 when the South African government announced the discontinuation of the Zimbabwean Special Permits and gave those affected 12 months to apply for mainstream immigration visas. At the expiry of the 12 months period, those who would not have succeeded in their applications would have had to leave the country or be deported.

The government’s decision has since been subject to court challenges by civil society organisations. The Pretoria high court ruled in June 2023 that the government’s decision was unlawful and irrational and ordered that the permits remain valid for the next 12 months. In light of the court losses and further appeals, the minister has since announced a further extension until November 2025 for both the Zimbabwe and Lesotho Exemption permit holders.

The government has also departed from the proposals in the 2017 White Paper and introduced a new White Paper (2023) which it says will overhaul the Citizenship, Immigration and Refugee laws. This has faced criticism from political commentators, academics, and refugee and migrant organisations who argue that the new proposals are misplaced and are based on false claims and poor logic. Some political parties have accused the governing African National Congress (ANC) of using the immigration issue for electioneering with no genuine interest in addressing the challenges of irregular migration and the inefficiencies of the department of home affairs, i.e., the country’s interior ministry.

Hirsch’s (2024) conclusion is apt in this regard: “The draft white paper gives the impression that the challenge of migration policy can be solved with tighter laws on refugees and citizenship.” Hirsch further highlights that, “the fundamental problem is the corruption and inefficiency in the permits and visa section of the department, which the white paper hardly mentions.”

Poverty, Unemployment and Xenophobia

The termination of special permits and the decision to depart from the 2017 White Paper occur within the context of increased restrictions and securitization of the migration discourse where migrants are being constructed as a security threat as well as a threat to the economic gains of a democratic South Africa. The country faces many challenges, including unacceptably high levels of unemployment which have breached the 32 per cent mark and much worse at 61 per cent amongst the 16 – 24 age group.

Poverty also remains high and politicians often use these challenges to create the perception that migrants and refugees are the problem, that they are responsible for unemployment and poor service delivery. Often, political rhetoric that casts foreigners as scapegoats for the country’s problems leads to xenophobic violence. The worst episode of such violence to date was in May 2008 when over 100’000 people were displaced and 62 killed.

Conclusion

South Africa remains an attractive destination for migrants from neighbouring countries as well as further afield on the African continent and from Asia, Europe, and North America. The country has had a long history of migration from neighbouring countries due to the contract labour system and the historical socio-cultural connections amongst citizens. But the response to migration has often lacked coherence and of late, it has been dominated by a shift towards restrictionism and the construction of migration and migrants as a threat. This can be observed in the policy proposals and the establishment of organs of state such as the Border Management Authority which deploys armed border guards to protect the country’s borders against irregular entry of migrants. While on the face of it, these seem to be laudable initiatives, the militaristic turn and the accompanying rhetoric are a cause for concern.

The country is also grappling with high unemployment, poverty, inequality, and a looming national election which has seen a rise in inflammatory statements by politicians which may fuel xenophobic violence. Thus, South Africa is at a crossroads regarding its management of migration where it needs to balance the need for skilled immigrants, high levels of unemployment and poverty and its responsibilities to protect refugees and asylum seekers.

References

Moyo, K., 2020. Dichte, Enklaven und der Alltag von Migrant*innen in Johannesburg. Verdichtung der Stadt?: Global Cases und Johannesburg, S.159.

Moyo, K. und Zanker, F., 2022. Keine Hoffnung für die "Ausländer": Die Vermischung von Flüchtlingen und Migranten in Südafrika. Zeitschrift für Einwanderungs- und Flüchtlingsforschung, 20(2), S.253-265.

Wilson, F., 1976. Internationale Migration im südlichen Afrika. International Migration Review, 10(4), S. 451-488.

Dr Khangelani Moyo is a Senior Lecturer and Researcher on Migration in the department of Sociology, University of the Free State – Qwaqwa Campus, South Africa. He has published widely on Migration in Southern Africa and his research interests include migration management, refugee governance, migrant transnationalism, spatial identity in the city and social vulnerabilities in the urban peripheries. He is a former FFVT fellow at the Centre for Human Rights Erlangen Nürnberg (CHREN) and DFG-TWAS Cooperation visiting fellow at the Africa Centre for Transregional Research (ACT), University of Freiburg, Germany.