Poor and also ageing - demographic change in BRICS states

Populations are ageing before the country has achieved the desired level of wealth. China's strategy could be a model for a new, joint agenda for developing countries. Whether they are successful is of global significance.

Demographic transition occurs when falling death rates and increasing life expectancy combine to set off a population boom, which continues until fertility rates decline. The process is typically driven by improvements in health and education which result in a falling birth rate and a reduced early and mid-life mortality rate, which in turn produces a gradual shift in the population ageing structure. (1) So far, no country has developed socioeconomically without an underlying process of demographic transition. (2) Demographic transitions, moreover, also produce an accelerated potential for economic growth associated with changes in the population age structure, specifically with a larger working-age population relative to dependent populations of youth and the elderly. (3) Consequently, economic development supports rising life expectancy and often fewer births per woman, ultimately producing an elevated share of seniors in the population.

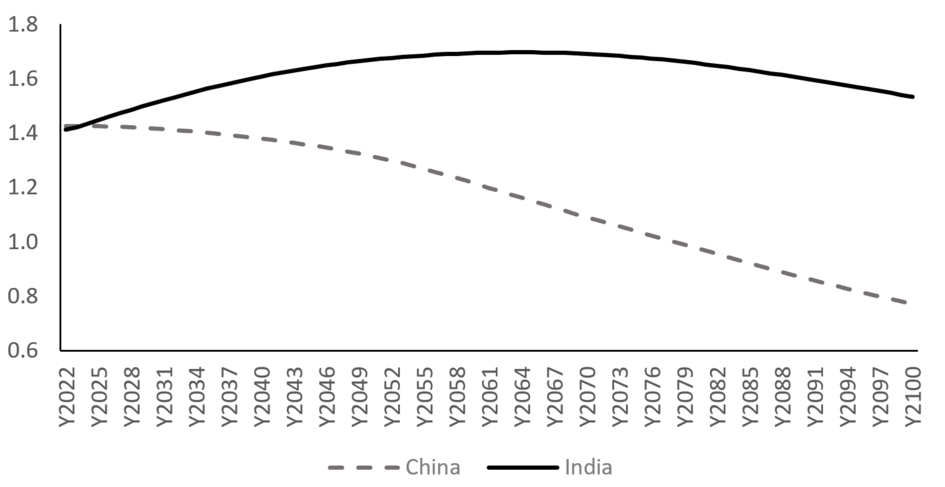

Recently released data confirmed a second year of population decline in China, alongside a rising share of elders. China is already home to more than a quarter of a billion residents over the age of 60, a number that is expected to rise for some years yet. Together with two broader epochal contemporary demographic turning points: the peaking of China’s population at 1.43billion at some point in 2022, and then in 2023 China ceding its crown as ‘the world’s most populous country’ to India. Consequently, links between demographics and development have been receiving more attention. (4) Projections from the United Nations (Figure 1) moreover, highlight that across the century China and India will mostly continue to demographically diverge: where China’s population is predicted to decline incrementally up to 2100, India’s is expected to peak in the early 2060s, at around 1.67 billion (some 200 million higher than China at peak) and then also decline.

Figure 1: Population forecast (medium estimates), China & India (2022-2100)

Such trends, and their global weight, may explain the elevated attention given to these trends by the BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – summit of 2023. (5) Where the declaration of the XIV. BRICS Summit hosted by Beijing in August 2022 focused almost exclusively on health in its reference to demographics, the August 2023, ‚Johannesburg II Declaration’ of the XV. BRICS Summit explicitly stresses cooperation in the area of population structure dynamics:

“We remain committed to strengthening BRICS cooperation on population matters, because the dynamics of population age structure change, and pose challenges as well as opportunities, particularly with regard to women’s rights, youth development, disability rights, employment and the future of work, urbanisation, migration and ageing” (6).

What might be in focus of this cooperation? And what exactly demographically are the BRICS looking at? A recent South African Institute of International Affairs Occasional Paper explores. (7)

Demographic Transition and the BRICS

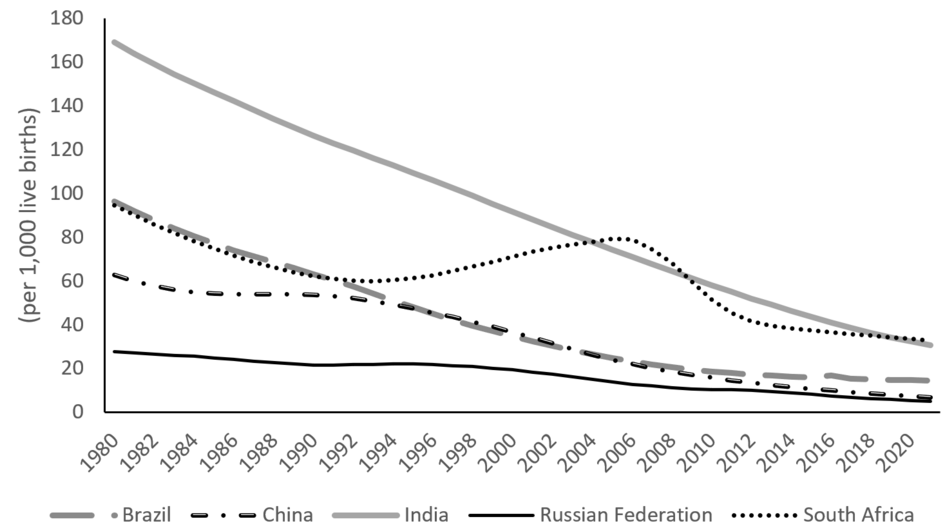

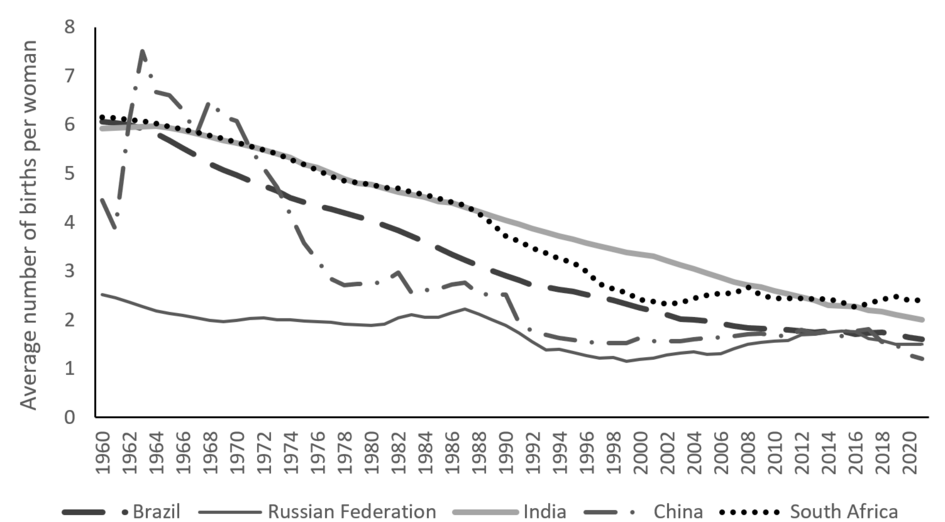

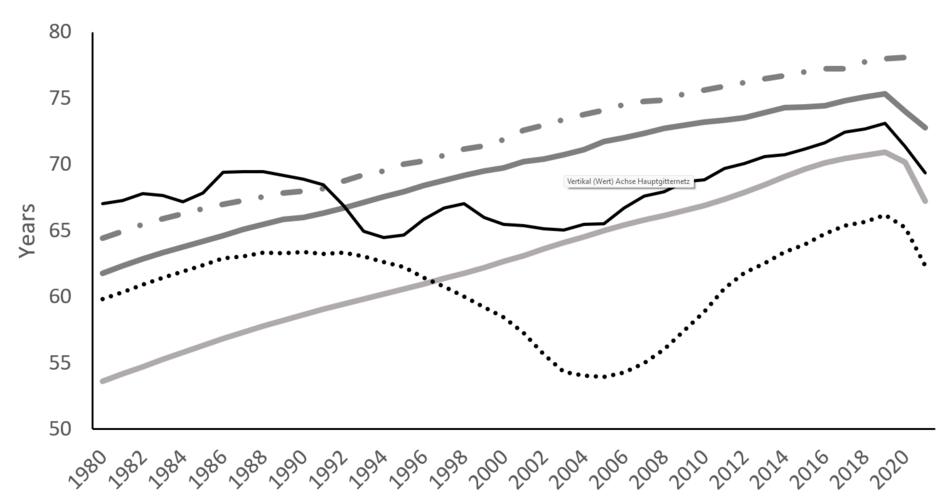

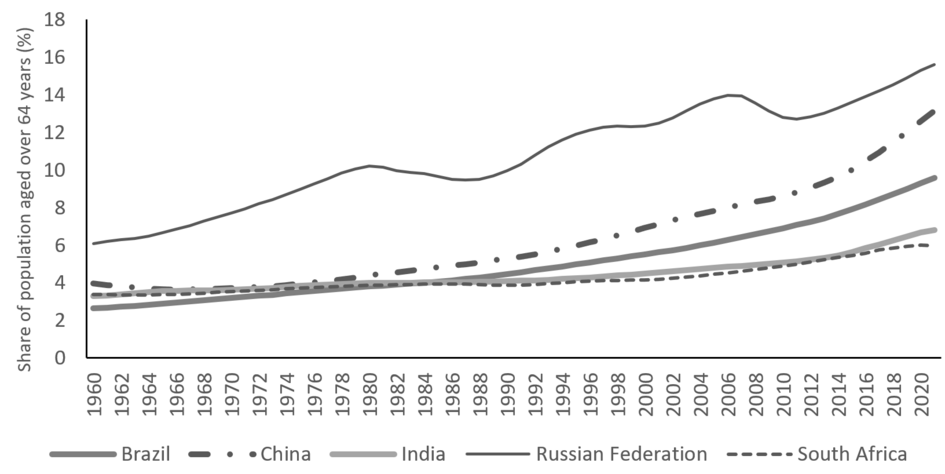

Figures 2-5 illustrate the progress of the demographic transition in the BRICS countries, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, according to four demographic indicators. As these figures illustrate all BRICS have experienced dramatic falls in child mortality and the total fertility rate (TFR), alongside a substantial increase in life expectancy and population share of seniors over recent decades – although the Covid-19 pandemic had a generally negative impact on the latter (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Under-Five Mortality Rate, BRICS (1960-2021)

Figure 3: Total Fertility Rate, BRICS countries (1961-2021)

Figure 4: Life Expectancy (years), BRICS countries (1961-2021)

Figure 5: Share of Population Aged 65 and over (%), BRICS countries (1961-2021)

The Speed of the Demographic Transition and a new BRICS Response

The speed of the demographic transition – in general this has been taking place with increasing speed – also has major socioeconomic implications for policy making. For example, not only does it impact the population share, size and age structure of the working-age population, and the burden on fiscal resources due to increased dependency and care for the aged – but also the amount of time to adjust to and prepare for these changes and their consequence. In healthcare, for example, as the median population age rises, there is an underlying shift from communicable to chronic illness. Alongside, lack of economic productivity and social safety net preparedness during a demographic transition risks economic stagnation and poverty of the elderly, especially among women who tend to accumulate lower savings during their lifetime and to live a few years longer than males. Table 1 presents the data for the year at which each BRICS country reached the stage of having the ‘ageing’ and ‘aged’ share of seniors in the population.

Table 1: Year of BRICS Country Reaching “Ageing” Thresholds

| Year reaching 7% aged 65 years & over (‘ageing’) | Year reaching 14% aged 65 years & over (‘aged’) | Time Gap (years) |

Brazil | 2011 | 2033 | 22 |

Russia | 1967 | 2017 | 50 |

India | 2023 | 2048 | 25 |

China | 2001 | 2023 | 22 |

South Africa | 2030 | 2059 | 29 |

Sources: For dates before 2021 the figure is taken from World Bank, World Development Indicators; for dates after 2021 the figure is an estimate taken from the UN, World Population Prospects.

Russia, the ‘oldest’ of the BRICS countries and first to embark on the demographic transition, enjoyed a 50-year transition and adaption period between the two ‘ageing’ thresholds. Younger BRICS countries are less fortunate, having only half the number of years to prepare for more intensive population ageing. Alongside Russia, China is the only BRICS country to have reached the second threshold. Like China, Brazil, predicted to reach the second threshold in a decade, will need to accommodate the necessary socioeconomic changes in just over two decades, and India in little over a quarter of a century.

Economic models tend to predict population ageing will diminish economic growth via both the factors of labour – a reduced labour supply – and capital factors, such as a reduced savings rate since people tend to draw down their savings in old age. These models, however, alsoimply that the effects can be shifted by policy changes around such variables as the retirement age, migration, and the adoption of productivity-enhancing technologies. (8) It has been argued that population ageing may itself directly stimulate automation-related innovation. (9) Moreover, the ‘weight’ of population ageing is unique to a given national circumstance. For example, whether seniors can vote (and whether they do if they can), the sustainability of pensions, and the retirement age compared to life expectancy all impact the ‘weight’ of population ageing. The BRICS countries have agreed to cooperate in related areas.It is likely they will do this through the BRICS think-tank, academic and business forums, and also possibly by encouraging the BRICS development bank, the New Development Bank, to invest in related studies and developments.

China as a Case Study and the Bigger Significance

Following a Smaller Families campaign in the 1970s and a One Child Policy implemented from 1980 to 2015, China’s TFR converged rapidly with the low TFR of much richer economies in East Asia, like Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. After the One Child Policy was implemented, however, China’s social sciences research community set about trying to understand the full set of prospective consequences. The late Chinese demographer, Wu Cangping, realised that China would inevitably get old before it had any hope of getting rich – the rate of its demographic transition was simply too fast. This in turn means that for the decades since, China has not just had an economic modernisation agenda, but also a demography-weighted one. One that seeks to prevent China, as a rapidly ageing middle-income economy, from suffering demography-led economic stagnation before its industrialisation agenda had succeeded.

Specifically, China feared it would not be positioned to replace its labour advantages with capital advantages, such as elevated human and technological capital levels. Worse, as population ageing intensified, it would need to redirect human and financial resources away from national development into care and pensions. (10) Ever since, China has taken steps to ensure its economy is at least relatively well-positioned to sustain population ageing amid ongoing economic development. (11) Table 2 summaries the agenda.

Table 2: Overview of China’s Demography Transition Economic Strategy

1980–1990s | Capture demographic dividend (labour-intensive investment incentives) |

Better educate the next (smaller) cohort to ensure elevated productivity | |

Create population ageing commission to set and operationalise an agenda preparing for population ageing | |

2000s | Prepare for elevated welfare and dependents such as a rising numbers of pensioners (health, social security, pensions) |

Scale up investment in science and technology (to support more capital-intensive instead of labour-intensive growth) | |

2010s | Promote capital-intensive investment; investment in universities, science, and technology |

Develop and incentivise an industrial strategy focused on the elderly(e.g., equipment and services needed by the elderly; pension and wealth management) | |

2020s | Push advances in technology; foster economic drivers to shift from labour quantity to labour quality and from labour quantity toward technology-related growth |

2030s | Ensure each cohort is progressively richer and more educated than the last – ie a constant if not rising effective labour supply, that rising labour-related productivity and output owing to rising productivity per worker, and even in the presence of a falling number of workers– so as to accommodate the older population’s needs without derailing national development |

Source: summarised from Johnston, Lauren A. China’s Economic Demography Transition Strategy: A Population Weighted Approach to the Economy and Policy. No. 593. GLO Discussion Paper, 2020. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/222235; Johnston, Lauren A. "Understanding demographic challenges of transition through the China lens." In The Palgrave Handbook of Comparative Economics, pp. 661-691. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021.

The chronology of China’s uniquely integrated approach to economic and demographic change presented in Table 2 can be summarised as a two-tier approach. The first tier comprises identifying and implementing policies to ensure China captured its low-wage demographic dividend for rapid economic development. The second tier concerned early incremental preparations, both direct and indirect, for the later period of intensive population ageing. That is, when China would be ‘old’ but not yet ‘rich’ and need to cater for large numbers of elderly at the same time as continuing economic development. (12) Johnston (2018 & 2021) outlines in greater details each phase in the unique case of China and also highlights its ageing-related systematic gradualism in policymaking. This is complemented by economic preparedness – readiness for moving into more capital-intensive growth, away from labour-intensive growth at the middle-income phase of development.

A Model vor a new BRICS Agenda?

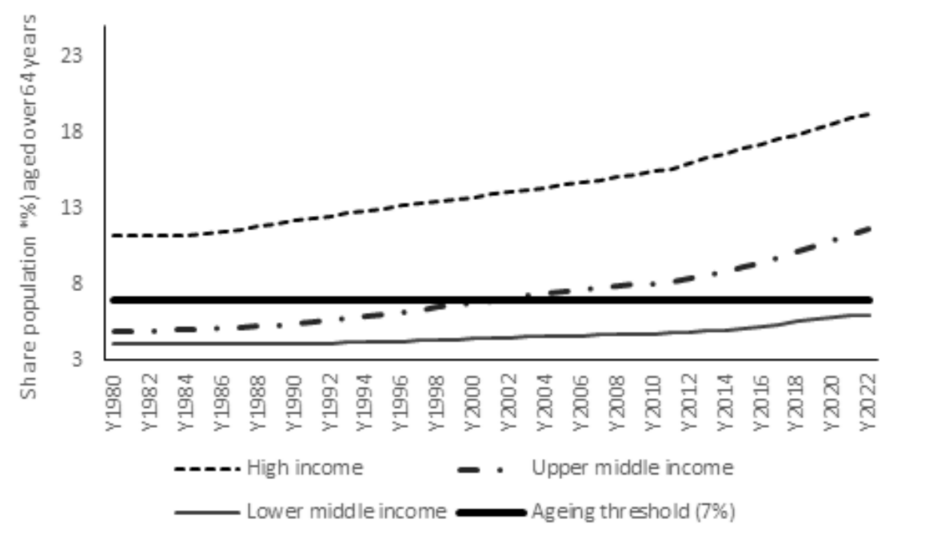

Since all five studied BRICS countries, like China, are already or will be old before they are rich, China’s early adoption of a demography-weighted development strategy may provide a reference point for the new BRICS agenda for cooperation on demographic dynamics. Beyond China, what is evolved by the BRICS countries in this context may be valuable to all developing countries. Figure 6 compares trends in the share of the senior population of countries by income group – high-income, upper-middle-income and lower-middle-income countries. (13) The trend toward an elevated share of seniors at gradually lower and lower per capita income levels across countries and time is clear. In other words, and unlike in the past, poorer countries are also getting older now too. That means many developing countries need to adopt a development path weighted for demographic transition, or at least one that is congruent with the changes in their own population structure – and those of their main economic partners.

Figure 6: Senior population share average by per capita income group

The BRICS agenda agreed in 2023 is not only important for the citizens of those BRICS countries, but also more broadly in setting policy precedents and solutions for global development. It is especially important for women, who tend both to live longer and to accumulate lower savings and wealth and hence face a greater risk of poverty in old age. Moreover, in times of intensive population ageing, young women can be exposed to pressures to form a family.

Finally, the importance of the BRICS countries to the global economy means that ensuring these economies can sustain population ageing – economically, politically, and socially – should be of global concern. The success of cooperation on demographic transition as envisioned in the Johannesburg II Declaration of the XV BRICS Summit is of great significance well beyond the BRICS countries themselves. (14)

References:

(1) Anzelika Zaiceva and Klaus F. Zimmermann, “Migration and the demographic shift”, in Handbook of the Economics of Population Agingvol 1 (Netherlands: North-Holland Publishing Company, 2016), 119-177; David E. Bloom et al, ‘Does age structure forecast economic growth?’, International Journal of Forecasting 23, no.4 (2007), 569-585.

(2) Renate Bähr, Dr Reiner Klingholz and Prof Dr Wolfgang Lutz, “When growth limits development,” Foreward in Africa’s Demographic Challenges: How a Young Population Can Make Development Possible, eds Renate Wilke-Launer, Matthias Wein and Margret Karsch (Berlin: Berlin Institute for Population and Development: 2011), 4-5.

(3) Choi, Yoonjoung. "Demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for demographic dividend." In Demographic Dividends: Emerging Challenges and Policy Implications, (Springer: Cham, 2016), 61-82.

(4) National Bureau of Statistics of China, Data Interpretation notice 410A04-0502-202301-0011, ‘Wang Pingping: The total population decreased slightly and the level of urbanization continued to improve’, January 18, 2023, http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/sjjd2020/202301/t20230118_1892285.html; India will become the world’s most populous country in 2023’, November 12, 2022, www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/14/india-will-become-the-worlds-most-populous-country-in-2023.

(5) The BRICS grouping has since expanded to include new members from January 1, 2024, which are not included in this analysis and the South African Institute of International Affairs paper from which it is taken.

(6) https://brics2023.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Jhb-II-Declaration-24-August-2023-1.pdf

(7) Johnston, Lauren, ‘Poor-Old BRICS: Demographic Trends and Policy Challenges’. https://saiia.org.za/research/poor-old-brics-demographic-trendsand-policy-challenges/

(8) eg. IMF, 2019, ‘Macroeconomics of Aging and Policy Implications’, https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/2019/060519a.pdf; and Liu, Weifeng, and Warwick McKibbin. "Global macroeconomic impacts of demographic change." The World Economy 45, no. 3 (2022): 914-942.

(9) Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, ‘Demographics and Automation’, The Review of Economic Studies 89 no.1 (2022): 1-44.

(10) Lauren A. Johnston. ‘The Economic Demography Transition: Is China's ‘Not Rich, First Old ’Circumstance a Barrier to Growth?’, Australian Economic Review 52, no. 4 (2019): 406-426.

(11) Johnston, Getting Old Before Getting Rich: Origins and Policy Responses in China’, 91-111

(12) Johnston. ‘The Economic Demography Transition’; Johnston, ‘Getting Old Before Getting Rich’.

(14) Suggestions for a future agenda are offered here: Johnston (2023) https://saiia.org.za/research/poor-old-brics-demographic-trendsand-policy-challenges/