Ahead of the Curve: What can Anticipatory Humanitarian Action Achieve?

Anticipatory Humanitarian Action (AHA) as an approach to dealing with crises is finding increasing support internationally. But it requires a rethink from donors who need to be prepared actually to utilise the window of opportunity between an early warning and a catastrophe - especially when it comes to finance.

As natural and human-induced hazards become more frequent and severe while we keep improving capacities to predict them, anticipatory approaches are gaining global attention. However, challenges persist, particularly in securing adequate funding and institutional support. To tackle this, we must collaborate to further enhance our forecasting capabilities and advocate for more resources. As we face increasing levels of risks and vulnerabilities, it becomes both a moral obligation and a practical necessity to take proactive, anticipatory measures to reduce the impact of impending hazards on people and communities.

Today extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more severe, resulting in catastrophic consequences for affected populations, with floods, droughts and storms accounting for up to 90% of hazards worldwide. In 2022 alone, the world experienced more than 380 natural hazards (1), claiming 30,704 lives and affecting 185 million people. The economic losses totaled approximately US$ 223.8 billion. Despite a rising demand for humanitarian assistance, responding to humanitarian crises has become challenging not only due to the impact of climate change but also escalating conflicts, access constraints and significant funding cuts.

Getting ahead of crises by anticipating them

To break this reactive and costly cycle, the humanitarian system requires innovation. Most humanitarian assistance is still only provided when communities have already experienced significant loss and damage. However, with the technical and monitoring capabilities available today, the majority of hazards, especially of a hydrometeorological nature, can be more reliably predicted. To meet or even reduce the need for humanitarian action, a shift away from mostly reactive to a more anticipatory approach is necessary. By taking an anticipatory approach to humanitarian action (see Box 1) – that is, by seizing the window of opportunity for action between a specific warning and before a hazardous event occurs – we can save lives and reduce costs and suffering, protect development gains, and support affected populations to prepare for disasters more effectively and quickly.

Box 1:

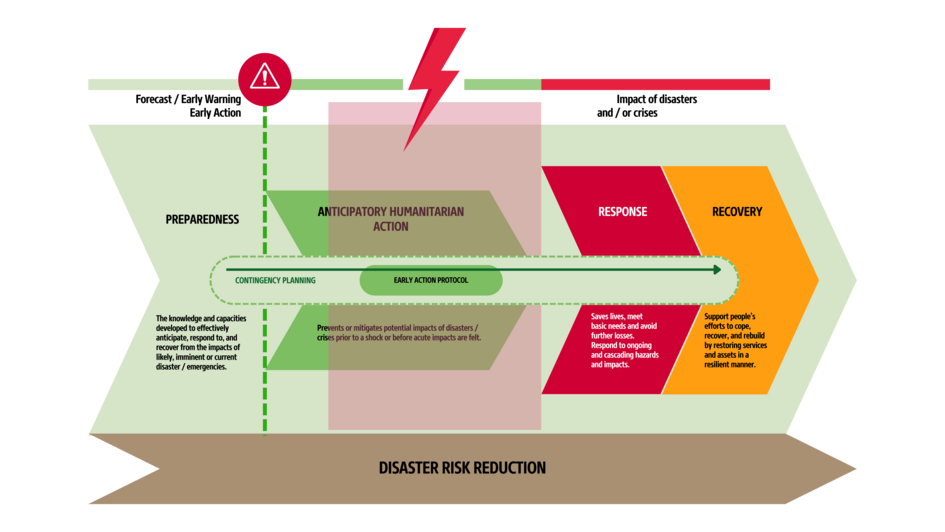

What is anticipatory humanitarian action (AHA) and where is its place in the disaster risk management (DRM) system?

Anticipatory Humanitarian Action (2) is a mechanism that allows for the implementation of so-called Early Actions (3) ahead of predictable or imminent risks, triggered by an operational impact-based forecasting and/or monitoring system with pre-set thresholds and an Early Action Protocol (EAP) that defines who does what and when as soon as the threshold is reached. This mechanism is then linked to pre-agreed financing, enabling the timely implementation of Early Actions. AHA is implemented in the time window between a specific early warning and the hazard or its peak impact (see graphic below). Early Actions can prevent or mitigate losses and damages and account for residual risk not covered by preparedness and other Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) measures. It is important to note that AHA efforts are distinct from preparedness efforts, as they are always undertaken for a specific, imminent threat.

Anticipatory approaches in the spotlight across sectors – but growing attention not always translate to immediate change

Today, Anticipatory Humanitarian Action (AHA) initiatives and projects have been developed in more than 70 countries worldwide. Furthermore, AHA is directly and indirectly referenced in various global frameworks and agreements, also from neighboring fields such as the development and climate change sectors. Addressing / Engaging with the approach across sectors emphasizes its importance to reduce risks, build resilience, and better prepare for crises holistically – at least on paper / in theory. In 2022, the G7 Foreign Ministers issued a statement on Strengthening Anticipatory Action in Humanitarian Assistance, affirming a common understanding of AHA. The Foreign Ministers also committed to scaling up and embedding AHA in the humanitarian system. What is yet missing are concrete steps of operationalizing this common understanding, for example, by using a joint reporting system on commitments.

Other initiatives that directly or indirectly support stronger AHA include:

Global initiatives:

- The G7/V20 (4) Global Shield Against Climate Risks launched at COP27 in 2022 is a financing mechanism focusing on increasing prearranged finance availability to address climate risks and close financial protection gaps, with concrete commitments from key donors. Evolving from the InsuResilience Global Partnership, the initiative aims to strengthen the financial protection and resilience of countries on the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) list of Official Development Assistance recipients vulnerable to climate- and disaster-related risks by providing and by facilitating more and better pre-arranged protection against these risks.

- The newly launched Getting Ahead of Disasters: Charter on Finance for Managing Risks (5) established by the UAE, the UK, Samoa, and the Risk-informed Early Action Partnership (REAP), which 41 countries and organizations have endorsed so far. This initiative sets the stage for a more resilient future by laying out five key principles (acting ahead of disasters to reduce risks (1), coordinating finance across sectors and timeliness (2), delivering pre-arranged finance for timely support (3), improving delivery systems for at-risk communities (4), localizing approaches (5)) aimed at enhancing the overall amount, efficiency, and effectiveness of finance and investments for AHA. However, it should be noted that the Charter is a non-binding declaration.

- The Early Warnings for All (EW4All) initiative, launched by the UN Secretary-General, aims to ensure that every human has access to early warnings by 2027. Hence, the initiative is inherently linked to AHA through its focus on providing timely and effective early warnings for various hazards since anticipatory approaches depend on such systems to trigger early actions and thus minimize the harm to people, assets, and livelihoods.

Regional initiatives:

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Framework on Anticipatory Action in Disaster Management is a regional policy to improve disaster risk management and minimize disaster impacts by ensuring that early warnings are translated into effective anticipatory actions. It emphasizes the importance of regional coordination, knowledge sharing and proactive implementation of anticipatory measures to reduce disaster losses and build resilience to future hazards.

- The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)’s Regional Roadmap on Anticipatory Action (IRRAA) was launched in a collaborative effort of Eastern African member states, Disaster Management Authorities, National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, and various stakeholders. Its objectives include to proactively safeguard populations from foreseeable hazards through the AHA approach. The roadmap draws a plan to develop tailored national and sub-national forecasts and early warning systems for different hazards.

Moreover, in the latest revision of the Grand Bargain commitments (Grand Bargain 2023 or GB 3.0), a unique agreement between some of the largest donors and humanitarian organizations, 66 signatory donors and aid agencies agreed on the need for scaling up preparedness and anticipatory action by establishing a common conceptual understanding of AHA and enhancing more flexible financing mechanisms to address humanitarian needs more effectively and efficiently[1].

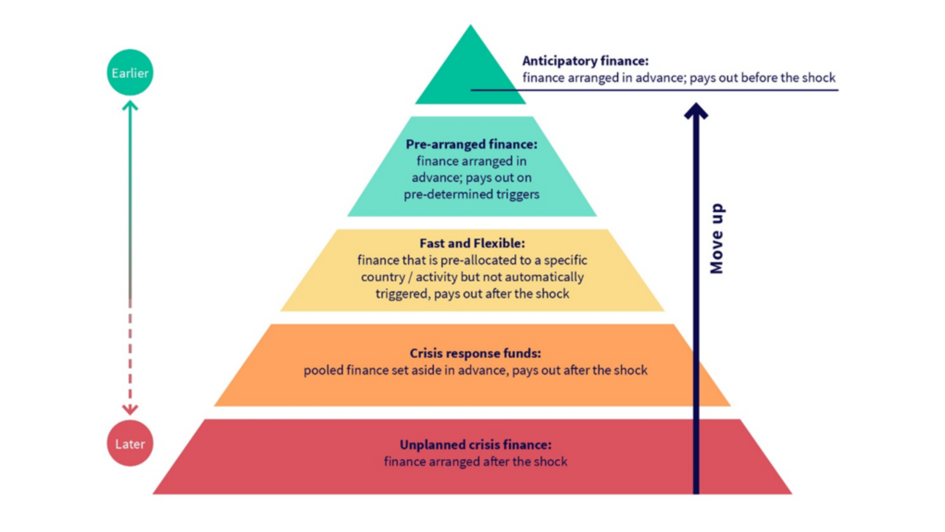

Despite the growing attention that AHA receives on the regional and international stage, it has not yet resulted in the necessary systemic shift in funding flows. According to REAP's study on Finance for Early Action the amount invested in Finance for Early Action is minimal compared to funds for unplanned crisis finance (see figure 2). One reason for the inadequate and ineffective financing of AHA, despite the consensus that it is faster, more effective, and more efficient, is the lack of alignment and coherence among donor institutions, governments, and aid agencies. Specifically, ad hoc and uncoordinated pilot programs and initiatives have been the norm for AHA.

Figure 2: Financing Early Action

Investing in AHA – a more dignified and cost-efficient approach

UN-backed appeals request US$ 46 billion to respond to worsening crises in 2024, which is less than the previous year's request of US$ 51 billion – an unprecedented decrease. The humanitarian system will focus on core life-saving activities and target fewer people. With a considerably smaller budget, and at the same time increasing risks of more severe and frequent extreme weather events driven by climate change, AHA offers an important additional tool to better manage these risks – also from a financial point of view.

Investing in AHA is expected to yield several positive outcomes, given that current challenges are being addressed. Significant attention has been paid to measuring the costs and benefits involved. Early Action demonstrates that timely procurement and stockpiling of humanitarian supplies (refer to Box 2) can result in significant cost savings. The challenges, however, arise from the inability to procure all items in advance at a lower price, the high cost of storing prepositioned supplies, and the limited shelf-life of certain items that may require disposal if a hazardous event does not occur within the relevant timeframe.

However, projects like the Emergency Supply Pre-positioning Strategy (ESUPS),a global project aimed at improving coordination and efficiency when it comes to pre-positioning of emergency supplies, show possible solutions through loan-borrowing policies, allowing organizations to temporarily share and exchange relief items among themselves, facilitating greater efficiency and resource utilization. The potential risk and associated costs of acting in vain when preparing for and responding to a crisis that has not yet fully materialized were also explored.

Despite this risk of occasionally acting in vain, the cost of a poorly guided AHA is outweighed by the cost of delaying intervention. There are many anticipatory measures that will bring benefits regardless of whether the crisis occurs or not. For instance, in the event of an incorrectly predicted drought, early vaccination and provision of fodder to reduce the risk of livestock disease will not have been in vain as they still improve health, body conditions and productivity of the livestock.

Also, World Food Programme’s (WFP) analysis of the Humanitarian Return on Investment (H-ROI) (6) for 14 flood-prone districts in Nepal (refer to Box 2) confirms the existing evidence on the benefits of early warning and AHA systems. AHA not only limits damages caused by natural hazards to vulnerable people and assets, saving a significant amount of money in immediate response, but also decreases long-term recovery needs and costs.

Box 2:

Evidence on the costs and benefits of early action

UNICEF/WFP Humanitarian Return on Investment (ROI) for Emergency Preparedness (UNICEF/WFP, 2015). This study evaluated the ROI of emergency preparedness and found that prepositioning of emergency supplies can yield HROIs of 1.6–2.0 and generate significant response time savings of between 14 and 21 days.

Department for International Development (DFID) Economics of Early Response (Cabot Venton et al., 2013). This study quantified the reduction in costs due to of procurement of goods early in response to humanitarian crises in Kenya, Ethiopia and Niger, and found that the cost of response decreased by between 11% and 45%. The study also modelled the impact of commercial destocking and vet services in Kenya and Ethiopia and found that these measures had a substantial return on investment (ROI), as well as reducing food deficits by between 9% and 72%.

WFPs humanitarian return on investment analysis for 14 flood-prone districts in Nepal (WFP, 2019) confirms the existing evidence on the benefits of early warning and anticipatory action systems. The AHA modality offers a process to limit damages caused by a natural hazard on vulnerable people (75% damage reduction) and assets (50% of damage reduction on crops and cattle) and thus save a significant amount of money in the immediate response (US$34 per dollar invested over 20 years compared to US$108). Moreover, it also further decreases long-term recovery needs and costs.

It is not solely a financial matter

The benefits of AHA can go far beyond financial questions. By minimizing losses and damages and reducing harmful coping strategies such as the sale of land and productive assets, the withdrawal of children from school to help with household chores, the taking out of unfavorable loans, or the skipping of meals, AHA can have long-term beneficial effects on malnutrition, education, health and resilience that are not easily captured in a short time frame. According to a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations analysis of the impact of disasters on agriculture and food (7), taking Early Action can increase resilience and mental wellbeing. Refraining from emergency sales of livestock due to feed shortages or economic instability, not borrowing, saving seeds for future harvests, are some examples of how AHA helps increase resilience. Provision of Early Cash before the onset of an imminent drought, addressed food insecurity in the North-East of Madagascar. In case of rapid-onset events like floods or cyclones, acting before the hazard occurs can even mean the difference between life and death. Therefore, the advantages of AHA are evident.

Consequently, with today’s technological capabilities that can provide accurate data to predict the likelihood and severity of impending hazards, our responsibility is clear: Taking action before a hazard occurs is not only a practical and cost-effective necessity, but also a moral obligation rooted in the protection of human life and the well-being of communities.

We must invest in forecasting, collaboration, and funding for a true paradigm shift

To build on today's successes and achieve a true paradigm shift, humanitarian actors must continue to address complex challenges. For one, forecasting and early warning capabilities must be further developed. This will require longer-term investments in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, an international document adopted by members of the United Nations that provides concrete actions to protect development gains from the risk of disasters, setting training programs and more collaboration and exchange between humanitarian organizations, research institutions and governmental stakeholders. Many governments and organizations still have limited capacity to collect the relevant data and produce and interpret forecasts.

Another challenge is the lack of earmarked funding for AHA. Although many countries have a well-established Disaster Risk Management (DRM) system with a variety of funding mechanisms available, analyses such as the one commissioned by Welthungerhilfe and Start Network to understand the financial flows for disaster risk financing in Kenya show that the vast majority of financial flows fall into either "disaster mitigation and resilience" or "timely response" (8) rather than “Early Action”. The Kenyan case study shows that scaling up financing for AHA is still a long way to go. Many countries will require financial management reforms before money can be triggered ahead of a crisis or to ensure that disbursed money flows quickly through government systems and out to communities at risk.

Finally, governments and donors may be hesitant to allocate budgetary resources for AHA based on forecasts, especially when uncertainty is high. Even with lower levels of uncertainty, pre-arranged resources can still be a challenging task. Therefore, it is necessary to effectively demonstrate the benefits of AHA through investment in better forecasting and monitoring systems as well as in research focusing on return on investments, documenting opportunities, and demonstrating the benefits of early interventions to overcome the fear of acting in vain.

Referenzen:

(1)With the exception of biological and extra-terrestrial hazards, and excluding technological hazards

(2) "Anticipatory Humanitarian Action" (AHA) is used by Welthungerhilfe as a synonym for "Anticipatory Action in Humanitarian Action". By doing so it stresses that actions always intend to prevent or mitigate potential humanitarian impacts.

(3) Impact-based forecasting is a structured approach for combining hazard, exposure, and vulnerability data to identify risk and support decision-making, with the ultimate objective of encouraging early action that reduces damages and loss of life from natural hazards.

(4) G7 under GER presidency and the Vulnerable Twenty (the V20) Group of Finance Ministersr

(5) "Getting Ahead of Disasters: A Charter on Finance for Managing Risks.”

(6) The return on investment methodology is widely used in finance for comparing the gains obtained from an investment (returns) with the costs of the investment over the course of its lifespan.

(7) Return on investment of anticipatory action interventions (fao.org)

(8) Uncovering the gaps: analysis of disaster-risk financial flows in Kenya from 2016 to 2022 - Anticipation Hub