Progress has been made in the fight against hunger, but conflicts are putting the success of recent years at stake.

Forced Migration and Hunger: 4 Misperceptions

Are hunger and displacement caused solely by natural events like droughts? No, it’s not that simple. Dr Laura Hammond identifies four misperceptions about forced migration and hunger that stand in the way of tackling the root causes of these challenges.

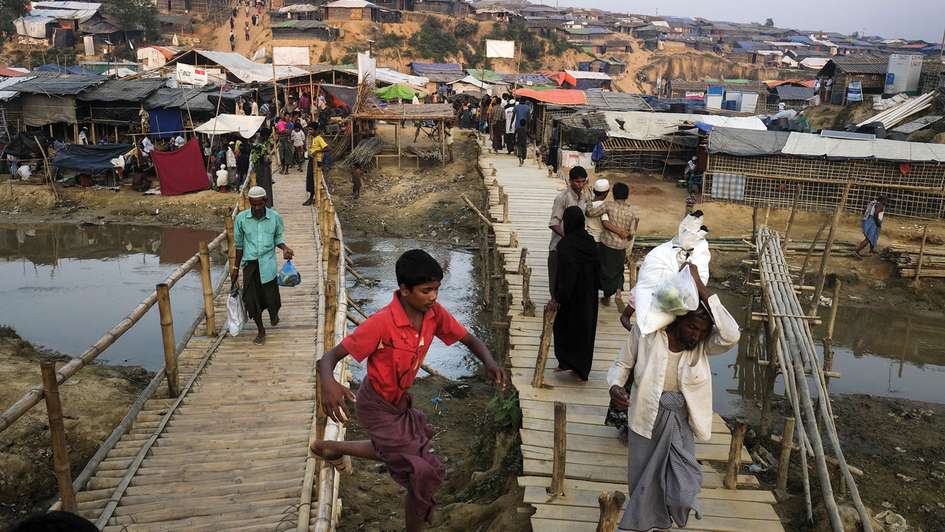

Across the globe, people are being forcibly displaced from their homes on a massive scale. There are an estimated 68.5 million displaced people worldwide, fleeing conflict, violence, and natural or human-made disasters. Hunger is a persistent danger that threatens the lives of large numbers of forcibly displaced people and influences their decisions about when and where to move. Hunger may be both a cause and a consequence of forced migration.

Four misperceptions and four solutions

There are four common misperceptions about forced migration and hunger that continue to influence policy despite considerable evidence showing that they are not productive. They stand as obstacles to tackling the root causes of displacement and to working toward effective solutions.

1. Hunger and displacement should be recognised and dealt with as political problems

Hunger is often understood to result from environmental or natural causes. However, natural disasters – droughts, floods, and severe weather events – lead to hunger and displacement only when governments are unprepared or unwilling to respond because they either lack the capacity or engage in deliberate neglect or abuse of power. Any effort to prevent or respond to forced displacement must engage with the underlying political factors. Support is needed for policies designed to prevent conflict and build peace at all levels, as well as for policies that reinforce government accountability and transparency, which make it more difficult for governments to shirk their duty to meet citizens’ basic needs for safety and food security.

2. Humanitarian action alone is an insufficient response to forced migration

The world’s response to forced migration is almost always to undertake humanitarian action – and nothing else. Assistance saves lives and provides basic shelter, health, water and sanitation, food security and nutrition – but it is not designed to support people over the long term. Most forced migration is protracted: people spend many years, even generations, being displaced. Displaced people and their host communities therefore need long-term support, including access to labour markets, land and productive resources as well as reliable access to affordable education and health care. This helps people rebuild their lives while they live as displaced persons or refugees.

3. Food-insecure displaced people should be supported in their regions of origin

The large numbers of refugees and migrants entering the European Union, particularly since 2015, have preoccupied many policymakers, but this attention has produced a misleading picture of the global refugee crisis. In 2015, refugees to Europe accounted for only about 6 percent of the global refugee population (UNHCR 2016). People facing food insecurity tend to seek the closest possible place of safety, because they often cannot afford to go any further. They may also prefer to stay closer to their homes to preserve social networks or stay in areas where they have ethnic, religious, or language affinities. The major displacement centres in the world are in poorer regions whose ability to absorb large numbers of displaced is extremely limited. Given their short-range movements and the disproportionate burden on host communities, food-insecure refugees and IDPs need to be assisted, if possible, in their regions of origin.

4. The provision of support should be based on the resilience of the displaced people themselves, which is never entirely absent

Despite being compelled to flee, forcibly displaced people never entirely lose their agency and resilience. Displacement is itself an act of agency, of moving in order to reach security and safety.

No matter how destitute they are, refugees and IDPs work to secure access to food, often in creative ways. Some supplement their food rations with food obtained from markets through trade or labour.

Some displaced persons share their assistance with relatives who have stayed in their original homes to protect their properties; they do this as a long-term investment in the future, even when the assistance they receive is barely enough to sustain them. Thus, a more holistic response to forced displacement would focus on supporting people’s livelihoods in their regions of origin and bolstering resilience in ways that support local markets and strengthen livelihood systems, thereby making people more self-sufficient and independent.

We need political solutions and longer-term development

Policy documents, international agreements, advocacy pieces, and academic writing often pay lip service to these four points but rarely incorporate them into action on the ground. Addressing the challenges effectively requires going beyond humanitarian responses, recognising the political solutions that must be encouraged and strengthened, and engaging in longer-term development efforts in the meantime.

This article is an edited and shortened version of Laura Hammond’s essay Forced Migration and Hunger published in the 2018 Global Hunger Index.