What to know about illegal fishing to put a stop to it

There is a lack of transparency in monitoring transnational criminal networks. International bodies must become more effective – and harmful subsidies be removed.

This article was originally published in the German-language "Fachjournal Welternährung" (World Food Security Journal).

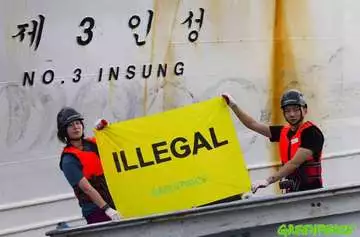

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing is one of the biggest threats to our oceans. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), it impacts the sustainability of fisheries, the livelihoods and food security of coastal communities, and the protection of aquatic ecosystems.

IUU fishing includes a range of offenses, including fishing without authorization, violation of flag state or local regulations, misreporting or non-reporting catches, and fishing of unmanaged stocks. It is often controlled by transnational criminal networks.

IUU fishing is highly profitable. The first and last global estimate of IUU fishing estimated in 2009 that the costs are between $10 and $23.5 billion annually, representing between 11 and 26 million tonnes. Developing countries are most at risk from illegal fishing, with total estimated catches in West Africa being 40% higher than reported catches.

Remote fishing vessels difficult to monitor

IUU is connected with distant water fishing (DWF). DWF industrial vessels can extend their operations to faraway places and sustain them for months without returning to port. However, DWF is often opaque and can lead to IUU fishing, says IUU Watch, an organization founded by Environmental Justice Foundation, Oceana, Pew Charitable Trusts, and WWF.

“Despite its importance to international trade and economics, the industry largely remains a mystery,” says the Stimson Center. “It is shrouded in an opaque operating system that limits information about where vessels operate, who owns them, the amount of fish that is caught, how fish is shipped and transshipped to market, the human labor practices onboard, and the access arrangements to other nations’ waters.”

Although digital technology and satellites offer “unique opportunities to support fisheries monitoring, control and surveillance (…), developed countries and multilateral organizations have been slow to exploit these opportunities and have failed to produce a single, effective, public global fisheries information tool,” says the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Better data management and closer collaboration are needed, alongside improved fisheries governance and more significant efforts to tackle corruption and curtail practices, including flags of convenience and secret fisheries agreements.

The biggest fishing nations

According to reported catches, in 2018 China (with 14.65 million metric tons (mmt)), Indonesia (7.22 mmt), Peru (7.17 mmt), India (5.32 mmt), Russia (5.11 mmt), the US (4.74 mmt), Vietnam (3.35 mmt), Japan (3.13 mmt), Norway (2.49 mmt), and Chile (2.12 mmt) are the biggest fishing nations. The EU caught in 2019 around 4.1 mmt.

Looking at the number of DWF vessels, five countries are responsible for 90 percent of DWF effort. “China and Taiwan alone account for 60 percent of DWF activity, while Japan, South Korea, and Spain account for about 10 percent each,” says SeafoodSource.

Regarding its DWF fleet size and global presence, China has the biggest DWF fleet. After depleting its domestic fish stocks, the Chinese fleet, like Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Russia, is now traveling further afield to meet the rising demand for seafood. The growth of China’s DWF fleet is supported by subsidies.

Fishing subsidies are estimated to be as high as $35 billion worldwide, of which $20 billion directly contributes to overfishing, UNCTAD estimates show. These subsidies are mostly paid to help offset the costs of vessel fuel, they also cover fisheries management and tax exemptions. They enable primarily industrial fleets to fish farther from shore and longer than they otherwise would. Without government subsidies, as much as 54% of the present high-seas fishing grounds would be unprofitable, a study found. Reforming fisheries subsidies could reduce overfishing and illegal fishing.

The role of China’s distant water fishing fleet

China’s DWF fleet has the technology, the capacity, and the incentives to travel to fish grounds located far away. The ODI investigation reveals that China’s fleet includes 16,966 vessels capable of DWF, five to eight times larger than previous estimates. The ODI report also found that at least 183 vessels in China’s DWF fleet were involved in IUU fishing. Trawlers are the most common DWF vessels in the Chinese fleet, applying the most destructive fishing method.

Other countries are also accountable for overfishing, but China is the most significant actor in global fishing. In comparison, the EU’s DWF fleet was 289 vessels in 2014, and the US had 225 large DWF vessels in 2015. This makes China’s low levels of transparency and monitoring over its DWF operations a reason for concern.

Flags of convenience

Shipowners and operators use flags of convenience (FoCs) to evade taxes and regulations of their home state, such as for safety and environmental standards and workers’ rights. FoCs can also help to protect vessel owners from legal action or scrutiny by obscuring who owns vessels engaging in illicit activity. Several of these FoC nations – notably Panama, Belize, Liberia, and St Vincent – are also recognized tax-havens. “Flags of convenience let illegal fishing go unpunished,” says a report published by Environmental Justice Foundation. Open registers with a large number of fishing vessels include Panama, Vanuatu, and Belize.

In the case of China, more than ninety percent of its DWF vessels fly the Chinese flag. However, as a flag state, China does not have a solid record of engaging with the international community and complying with Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs). China is its own flag of convenience.

Half of China’s DWF vessels are believed to operate in areas controlled by regional fisheries management organizations (RMFOs), but China has joined only seven of them. In comparison, the European Union – with a fraction of the Chinese fleet (less than 300 vessels) – participates in 17 such organizations.

Of the 183 DWF Chinese vessels suspected of IUU fishing, 89 are long-liners, our research shows. Longliners set out fishing lines up to 100km in length, each with up to 3,000 hooks. They use electronics to find a school of fish and then, using speed boats, haul the line through it.

It seems that the ownership of those vessels is highly concentrated. Just ten Chinese companies own almost half of the vessels suspected of IUU fishing. Many of the biggest companies behind the fleet are state-owned or parastatal. But it is unclear whether the Government of China has a comprehensive overview of its fishing fleet.

The DWF hotspots – threatening local communities

Much of DWF takes place in or just outside the territorial waters of low-income countries that often have insufficient monitoring capacity. Thus, DWF in low-income countries is often associated with unsustainable levels of extraction and IUU fishing activities.

The impact on local fishing communities is enormous. DWF poses risks to the sustainable use of marine resources in low-income countries, and people’s jobs and food security dependent on these resources. But this is about the loss of opportunity too. In a previous report, we estimated, for example, that with the right policies in place, more than 300,000 new jobs in fisheries could be created in western Africa.

Our study shows that 518 Chinese vessels are flagged to African nations, mainly in West Africa, where enforcement measures are typically limited, and fishing rights are often restricted to domestically registered vessels. It is no secret that 20 percent of the global IUU catch is estimated to come from just six West African countries (Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, and Sierra Leone).

Chinese vessels are often registered to local “front” companies under secret agreements but are connected to Chinese interests. This allows them to fish in local waters that local fishers should sustainably exploit and siphon the fish off to Chinese markets. As a result of these ill-designed agreements, more catch is licensed than stocks can tolerate, local fishers lose income and governments tax revenues.

The Pacific – the world’s most fertile fishing ground, which supplies well over half of the world’s tuna – also falls victim to illegal fishing, with up to one in every five wild-caught fish illegally caught.

The Ecuadorean navy recently found a vast fishing fleet of around 340 Chinese vessels just off the Galápagos Islands. The flotilla was taking advantage of the abundant marine wildlife that travels in the waters between the Galapagos and the mainland. This discovery is just the latest incident in a series of breaches and violent encounters. It should raise the alarm about how far and how impactful uncontrolled distant-water fishing is.

Some of this activity is illegal. For example, reports indicate that some of these vessels switch off their satellite communications in breach of the rules.

In the Pacific, the 17 nations and territories of the region directly control their territorial waters. Pacific Exclusive Economic Zones generate US$26bn worth of tuna, but the islands receive merely 10 percent of that value. Pacific countries seldom even crew fishing boats and make money only on the licensing.

What to do

DWF nations should take steps to demonstrate leadership. These include requiring all DWF vessels to enter a centralized, publicly, and internationally accessible registry, with details on holding companies as well as subsidiary owners; removing harmful subsidies; ratifying the Agreement on Port State Measures; joining regional fisheries management organizations and complying with their obligations; increasing monitoring, compliance, and enforcement efforts of larger, state-owned, companies with the most extensive DWF operations; strengthening bilateral cooperation and capacity-building.

Coastal developing countries can support global efforts to combat IUU fishing by enforcing existing regulations on registration and tackling phony flagging of DWF vessels. All international fisheries agreements should be publicly available. These countries should also ratify the Agreement on Port State Measures.

Finally, international bodies and agencies need to be more effective, including monitoring, information-sharing, and prosecution of vessels and companies suspected of IUU activities. They should de-list IUU vessels and companies from import/export agreements and support coastal states to combat IUU activities in their waters.

Miren Gutierrez is a Research Associate with the Overseas Development Institute, published data-based reports on fishing. She holds a PhD in Communication and has been the Executive Director of Greenpeace Spain, Inter Press Service Editor in Chief, and a journalist based in Hong Kong, Panama, New York, and Rome, writing and researching for El Mundo, El País, The Nation, Wall Street Journal, UPI and Transparency International.